Guest Appearances

- Guest Conductor, Seattle Symphony Orchestra

- University of Montana Wind Ensemble tour of Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, Michi- gan, and Canada

- Guest Speaker and Conductor, cbdna National Convention, Ann Arbor, Michigan

- Guest Conductor, menc, Northwest Division Convention, Missoula, Montana

- Guest Professor, Eastern Kentucky University

- Member, Research Board, The Conn Corporation, Elkhart, Indiana

Articles and Monographs

- David Whitwell, “Bach and Wind Music of the 18th Century,” The Instrumentalist, November 1966.

- David Whitwell, “Author’s Rebuttal I,” Music Educators Journal 53, no. 3 (November 1, 1966): 14–20, https://doi.org/10.2307/3390836

- David Whitwell, “Liszt: His Music for Winds,” The Instrumentalist, December 1966.

- David Whitwell, “Schumann: His Music for Winds,” The Instrumentalist, January 1967.

- David Whitwell, “Mendelssohn: His Music for Winds,” The Instrumentalist, 1967.

- David Whitwell, “Bach’s Sons: Their Music for Winds,” The Instrumentalist, March 1967.

- David Whitwell, “George Frederick Handel: His Music for Winds,” The Instrumentalist, April 1967.

Recordings

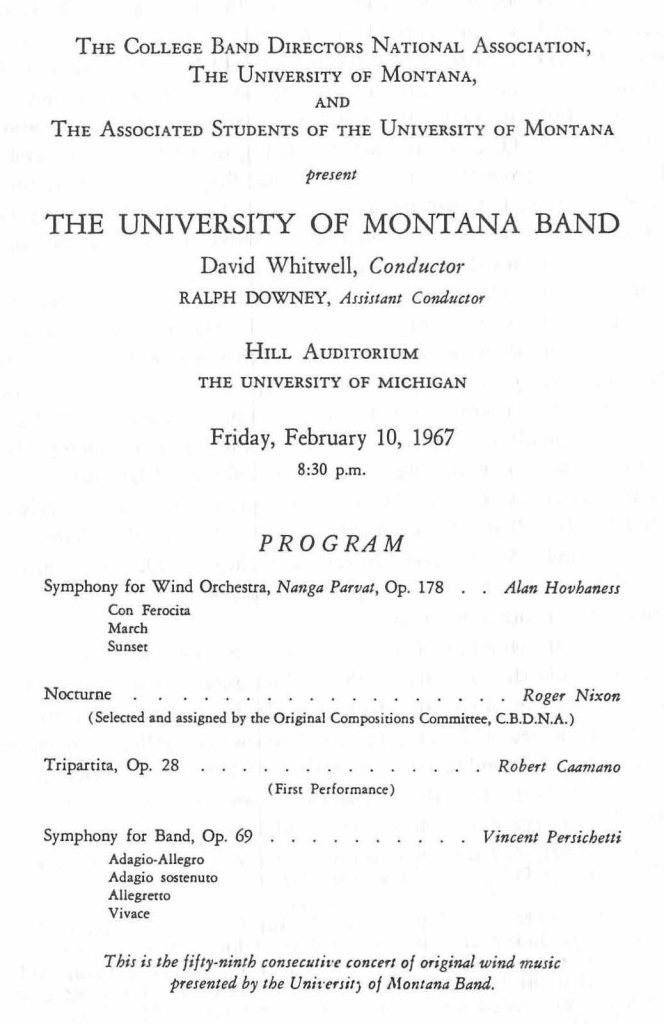

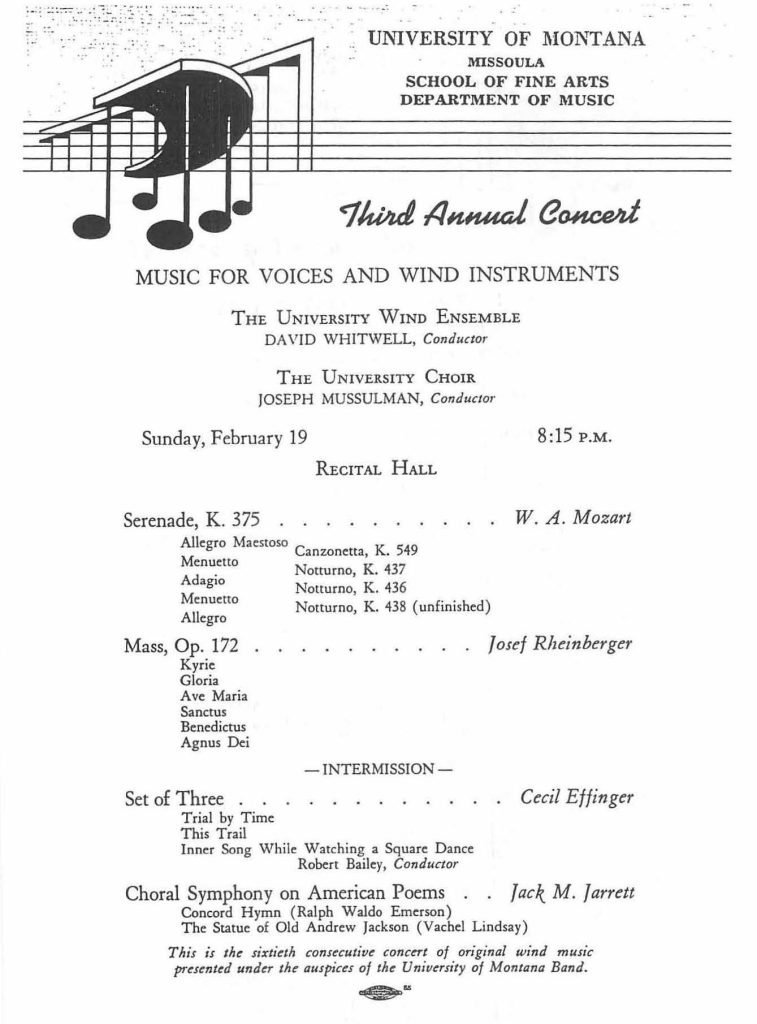

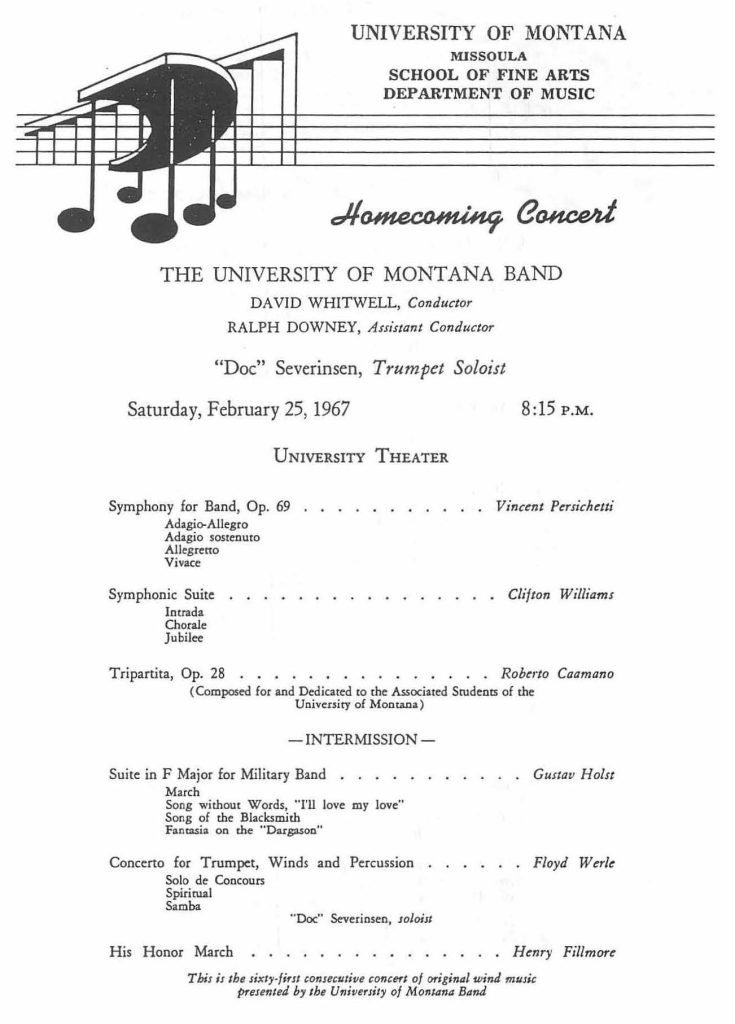

University of Montana Band, At College Band Directors’ Twenty-Fifth National Convention, February 10, 1967, David Whitwell, Conductor

- Alan Hovhaness, Symphony for Wind Orchestra, op. 178 (“Nanga Parvat”)

- Vincent Persichetti, Symphony for Band, op. 69

- Robert Caamano, Tripartita, op. 28

My decision to leave the University of Montana, and the band profession, at the end of this year, coming as it did after four increasingly successful years, and climaxed by a performance at the CBDNA National Convention, surprised many people. A number of things contributed to this decision and I did not make it lightly.

First, Giselle and I had begun to be concerned with the isolation of Missoula. Here one had to create one’s own art and culture. One can do this of course, but one soon becomes aware of the need for outside artistic ideas. We began to give this a lot of thought after the faculty’s lack of interest in our State Department tour of South America, but the issue really came into focus with a concert by the Houston Symphony during the Fall. The appearance of the Houston Symphony was the first in Missoula by any major orchestra in anyone’s memory and naturally it was an event awaited by all of us with great anticipation. As it turned out, Missoula was the first stop on a tour by the orchestra and they flew from Houston the day of the concert. Their plane was not a jet and so they were nearly all air sick when they arrived. The conductor, Sir John Barbirolli, was at the end of his career and not in good health to begin with. In addition, on this evening, he appeared to be drunk and had considerable difficulty walking to the podium and maintaining his balance while conducting. In sum, it was a terrible concert. As I went out into the lobby for intermission I was disappointed, angry, and felt like asking for my money back. I was astonished to find all of my colleagues on the music faculty, on the other hand, delighted and praising this wonderful concert. I knew then I did not want to ever live in isolation so long as to think a concert like this was good.

Second, by this season I had become tired of the marching band. Some things about designing and watching marching shows come to life on the field are truly fun. The problem for me was that the fun was not in proportion with the enormous amount of hours necessary to make it happen. The first three years I did this it was all a new experience for me, but by this year I began to have that deadly feeling that I was in a rut. Had some important university at this moment offered me a position as Director of Bands, with someone else doing the marching band, I probably would not have left the profession at this time. However, the only school which called was Syracuse and the chairman wanted one man to do everything, as in Missoula. It was a much more famous school, but the same rut.

Third, during my years at Montana I frequently had people say to me, in effect, “You are so good, you should be an orchestra conductor!” I began to give this serious thought when I had the opportunity to guest conduct the Seattle Symphony, which visited Missoula this year, and about a dozen of the members of the orchestra came running up afterwards and said, “Boy, we wish you were our conductor!” Their conductor, Milton Katims, who had been principal viola under Toscanini in the NBC Orchestra, was also generous in his praise for me. I had a discussion with him at this time regarding how one breaks into this field. His answer was a simple question, “Are you Jewish?” When I said “no,” then he said unless you are very wealthy, or have very wealthy friends, you will not have a major career.

Morton Gould and Alan Hovhaness were traveling with the orchestra and so I was able to have each of them guest conduct a rehearsal with my band while they were in town. Gould conducted his Symphony1 and proclaimed there was absolutely nothing he could add to the reading. I had invited Hovhaness to my home one evening and I remember being in fear, as he was so tremendously fragile, that he might bump into a chair and kill himself! I played the tape of our Ann Arbor performance of his Symphony Nr. 72 and as he listened he began to swing slowly back and forth lost in his thoughts. Suddenly, in a place where I had taken the tempo slightly faster than that marked in the score, he awoke from his meditation, threw his hand to his face, and moaned in agony. It was a very powerful lesson for me and ever since I have thought long and hard before ever changing a tempo, however slightly.

My feeling was that if I were ever going to make a break and explore the world of orchestral conducting, it would have to be now, when I was still young and before we started a family. I also knew that if I didn’t do it I would always wonder what would have happened if I did.

The final things which confirmed my decision to resign were associated with the University of Montana Band’s invitation to perform before the national convention of the CBDNA in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in February 1967. This was a very big event as it was the twenty-fifth anniversary of the organization and the first time the convention had been held at Michigan, where William D. Revelli, Director of Bands, was also the founder. A national tape competition was held and we were selected to play in the company of some very famous bands: the Ithaca College Band, Walter Beeler, conductor; the University of Minnesota Concert Band, Frank Bencriscutto, conductor; the Michigan State University Concert Band, Leonard Falcone, conductor; the Ohio State University Concert Band, Donald McGinnis, conductor; the Luther College Concert Band, Weston Noble, conductor; and, of course, the University of Michigan Symphony Band itself under Dr Revelli.

It should have been apparent that it was a very great honor for the University of Montana to be included in such company. While the administration gave its due congratulations, they were not so swift in assuring the financial support needed for the trip. Of course, I had to begin making plans for the tour long in advance and had to more or less assume I would be able to actually fund the tour when the time came. It seems remarkable today that for this tour, with concerts in Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, Michigan, and Canada, I only needed $7,000, which included flying us all to Chicago and back! In the end, I only heard from the administration that they would support the cost on the weekend before we left, and during all that time my neck was very far out. This was a strain on me and the fact that the university was so slow in offering its support for so important a cause contributed to my desire to leave. The final link in the chain of events which led to my resolve to resign occurred after the CBDNA performance in Ann Arbor. Our concert there was unusually successful, one of those rare concerts which seem to remain in people’s memories. For more than fifty years after the concert I have had colleagues recall this concert to me. There were several factors which made this level of impact possible. Perhaps the most important, and one often mentioned to me, was the fact that among this lineup of famous bands no one expected much from this small university of five thousand students in Western Montana. We simply caught everyone by surprise. It also was to our advantage that we shared this concert with the Ohio State University Concert Band. We appeared in tails and they in old, ill-fitting, drab gray uniforms. Some people felt the two performances were as strongly dissimilar in character in other ways as well.

Another important contribution to our success was the tour of nine concerts beforehand. Not only did this help polish the performance, but it gave us a great deal of confidence. We had often been praised in the Northwest, but none of us knew what our reception would be in the famous old band towns like Joliet, Illinois, and Elkhart, Indiana. The really enthusiastic reception we had in every city helped all of us to believe in ourselves. Samples of the letters we received from these earlier concerts will perhaps reveal how much confidence we gained.

I can honestly say that your performance was the finest I have ever heard.

Mr Harry Pfingsten, Cleveland, Ohio

To hear a concert band play with the finesse and sensitivity of a highly trained symphony orchestra is an event which comes once in a lifetime. Mr Burger, our band director at Academy High School, said it best. He said that the Montana Concert Band was by far the most eloquent band that had ever graced their stage—or ever would!

Mr Carl Peterson, Erie, New York

The performance by the Montana Band is one of the finest concerts I have been privileged to hear anywhere.

Few people, I regret to say, can realize and appreciate the magni- tude of the job that must be done by the director to achieve the degree of musical dedication and perfection as well as self-discipline necessary to develop a band such as you brought to Elkhart.

Our sincere congratulations and appreciation to you, your staff and the band for an outstanding, inspiring performance.

Ronald Miethe, Elkhart, Indiana

Finally, it was to our advantage that three of the four compositions we played were unknown to the audience. These included a demanding symphony by Hovhaness3 and the premiere of a South American work.4

I was very excited and pleased by the opportunity to return to the stage of Hill Auditorium after eight years and to have the opportunity to appear before all my former teachers and numerous former fellow students who lived in the state. In addition to the enthusiastic congratulations from all these people, I was very moved by the comments of literally hundreds of fellow college band directors who came forward to see me after the concert. Many more conductors and members of the audience wrote to me in praise of this concert. Perhaps a few quotations will demonstrate the impact these Montana students produced.

You shocked everyone by turning in the most stunning performance of the whole conference. Thank you again for an inspired performance that we shall not forget.

Mrs Jack Snider, Lincoln, Nebraska

Thank you from the bottom of my heart for the wonderful concert you performed in Ann Arbor. The Montana Band is the band of the future. Your band with its young members and conductor display a thrilling sense of excitement for your music, and your performance transfers this excitement to your audience.

Prof. Thomas Morse, Eastern Michigan University

It was a truly virtuoso performance on the part of both conductor and players and the choice of music was ideal. Everyone concerned is deserving of the highest praise.

Harold Bachman, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida

Your concert was fine! The band did you proud with this difficult program, and your conducting looked great. It was, truly, a most enjoyable evening.

Prof. Elizabeth Green, University of Michigan

You certainly did your part in upholding the honor of wind playing with your splendid performance in Ann Arbor. The band and you did a superb performance and we of the Northwest were proud of you and happy that you did represent us in the magnificent fashion you did.

Prof. Walter Welke, University of Washington

Recently it was my privilege to compare Mr David Whitwell with seven other leading college and university conductors. So impressive was his performance, I asked him if he would consider leaving his present position for an orchestral conducting job. His sensitivity, fine musical tastes and infinite control over his group of musicians marked him as the outstanding conductor at the most recent convention of College Band Directors.

Jack Snider, University of Nebraska

At the recent CBDNA National Conference, his performance was outstanding. His band played a difficult program of wind music with great finesse. He was the only conductor to conduct all works without a score.

James Jorgenson, University of Redlands

Mr Whitwell is obviously extremely talented. He conducted an entire program, including contemporary music, without score. The performance was tightly controlled and one of the most musical I have heard. He knew exactly what he was after and the results were remarkable, especially considering the relative immaturity of his players.

Paul Bryan, Duke University

Just a note to tell you how thrilled I was to hear your wonderful band at the recent CBDNA meeting in Ann Arbor. The performance was most enjoyable and the band was superb in its performance.

Prof. Jack Lee, University of Arizona

Congratulations to you and your fine band for your most successful appearance in Ann Arbor. It is a great joy to note the Montana Band among the other top college bands in the country. Please consider this note a hearty, “thank you,” from all Montana bandmasters.

Mike Roberty, Presdient, Montana Bandmasters Association

In terms of simple exhilaration, this concert in Ann Arbor was certainly at the highest moment of my career to this time. I have quoted these reactions to the concert in order to help the reader understand the impact on me of what happened following the concert when I walked across the street to the reception!

The reception was held in a large hall which had a buffet table at one end for the University of Montana Band and a buffet table at the other end for the Ohio State Band—clearly we were not supposed to mix with the Big Ten. Audience members walked back and forth, with the very obvious exception of William D. Revelli and his assistant, George Cavender. Their refusal to walk over and congratulate the students and me was noticed by many people. Leaving aside the fact that he was the official host for this evening, one would at least think he would have been happy to see one of his former students succeed. Clearly his opinion should not have mattered so much to me, in view of the wonderful reaction of everyone else, but the fact is this calculated and public snub caused me to question once again whether I really wanted to be part of such a profession. This question filled my thoughts on the return trip to Missoula and I decided to tender my resignation upon arrival.

My resignation came as a great surprise to the faculty at the University of Montana and I received many expressions of sorrow for my decision to leave. I was particularly touched by the President, who wrote, “I suspect we won’t be really able to replace you.” Before my final concert, the Chairman of the Drama Department, Bo Brown, published a tribute in the town newspaper, which said in part,

His going will be strongly felt not only in this western Montana community but in the entire state of Montana. Few men have done so much in such a short period of time to bring to near perfection an organization which has gained national recognition for the University and the state.

Tonight’s concert will clearly demonstrate the artistry of this young musician. Composer, music researcher, articulate classroom teacher, and a splendid instrument player himself, his many talents have added pleasure to our listening hours. Missoulians would do well to turn out tonight to hear good music, excellently directed—and to honor a dedicated artist who we trust will carry with him thoughts of our appreciation.

At one point during the year, as I was coming to question staying in the band profession, I read a book by John Warrack which said something to the effect that composers would never take wind instruments seriously. Out of curiosity, I sent this quotation to a number of famous composers and received lengthy replies from a number of distinguished composers, including Ingolf Dahl, Henk Badings, Alan Hovhaness, Walter Piston, William Schuman, David Diamond, and Aram Kachaturian and they all objected to this idea in the strongest of terms.

I also published another eight articles for my series on wind music by major composers in The Instrumentalist this year. In addition I had the opportunity to make some interesting professional trips. I had been appointed to a research committee which met at the Conn factory in Indiana. The committee itself was a waste of time, but it did give me a chance to break the isolation of Missoula, as well as visit with colleagues from throughout the nation.

I was also invited to give my first conducting clinic at the university level, at Eastern Kentucky University at Richmond. I remember this small university was situated on one side of a highway and across the road was a great estate which belonged to an elderly lady. Apparently each president, upon arriving at the campus and seeing all this land, made an attempt to purchase her property. In visiting the current president at a social occasion, he told me he did the same thing and this lady had her lawyer put an end to these intrusions by making an offer to buy the university!

I resigned from my position at the University of Montana with absolutely nothing planned for my future. My one clear thought about trying to break into the orchestral world was that I had no interest whatsoever in conducting a community orchestra. I would either break in at the top, or not at all. The first opportunity which presented itself was the announcement of the annual Dimitri Mitropoulos International Conductors Competition. I applied and asked a number of colleagues to write letters of support, which they did in a very generous manner. When I was not accepted to even compete, it became all too clear to me that success in the academic world was simply irrelevant in the professional world.

The only other course of action I could think of was to try to attach myself to some famous conductor as a protégé. For this purpose I asked a few men in the profession to write a letter of introduction and following are excerpts from some of these letters.

David Whitwell’s sensitivity, fine musical tastes and infinite control over his group of musicians marked him as the outstanding conductor at the most recent convention of college band directors.

Prof. Jack Snider, University of Nebraska

I feel David Whitwell is one of America’s most outstanding young conductors.

Prof. Wayman Walker, Colorado State College

Dr Whitwell’s conducting shows the understanding of a sensitive and thorough musician. He needs no score in performance and his baton technique is smooth, lucid and expressive. I am sure his musicians have the utmost respect for him.

Prof. Maurice Brennen, Willamentte University

The considerable ability of David Whitwell as a conductor is grounded in thorough musical scholarship and outstanding musical talent.

Mr Whitwell’s impeccable musicianship and extreme attention to detail are respected by musicians and audiences alike. He has the rare ability to establish complete musical communication between himself and his musicians and the results, in terms of excellence of performance, are remarkable.

Prof. Donald Carey, University of Colorado

Dr Whitwell is recognized as one of the outstanding college band directors in the nation today. Given the opportunity he will prove himself as one of America’s outstanding young conductors.

Prof. Norman Hunt, Sacramento State University

From a visual point of view, Dr Whitwell is an exciting conductor to watch. His movements are always in complete character with the music he is doing and they constitute an artistic performance in themselves.

Dr Whitwell has a remarkable musical memory which is the envy of many of his colleagues. I have never seen him conduct from a score.

Prof. Roger Heath, Purdue University

Although it is perhaps somewhat less important than the previously mentioned items, it should be added that Mr Whitwell looks good conducting. He is personable, graceful, straight, and gracious on the stage.

Prof. Stuart Ling, College of Wooster

Dr Whitwell’s knowledge of music is profound and this understanding is always reflected in the sensitivity and authoritative performance of the music he is at that time conducting.

I know of no one that I could or would endorse as highly.

Prof. Edmund Sedivy, Montana State University

I consider Dr David Whitwell to be one of the most outstanding young conductors of serious wind music in the country today.

Prof. Justin Gray, California State University, Fullerton

I seriously consider Dr Whitwell as one of the “bright lights” of the young conductors.

Prof. James Kerr, Wichita State University

David Whitwell is, in my opinion, one of the most promising young conductors in the field today.

Prof. Donald McCathern, Duquesne University

I am sure that he is capable of handling most professional conduct- ing positions currently.

Prof. H. Robert Reynolds, California State University, Long Beach

I have written letters to both Ormandy and Ehrling to express to them my reaction to your work, and I do hope they will help you along your chosen path.

With all best wishes to you.

Milton Katims, Conductor, Seattle Symphony Orchestra

I then wrote to all the major conductors telling them of my background and my desire to study with them. I received some encouraging replies and so I asked for a two-week leave from the university to go back East and talk with some of these men.

I had an expression of interest from George Szell, conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra, but because I had heard that he demanded extensive piano skills of his conducting students I decided not to follow up this opportunity.

My first actual appointment was with Howard Mitchell, conductor of the Washington National Symphony. He was perhaps a man of some talent, but by the time I met him he was tired and frustrated by his near total lack of success with the Washington critics. He asked to see me after an afternoon concert in Constitution Hall. After the concert I entered the ground level musicians door where I immediately noticed the strange silence prevailing as the musicians were putting away their instruments. From my professional experience this was usually a jubilant moment. In this silence I suddenly heard a scream from the stage level above, a scream it turned out belonged to Mitchell. It turned out that they had just returned from a tour, upon which the manager had been hospitalized. A member of the orchestra had volunteered to serve in his place and had mistakenly posted an incorrect personnel list for some upcoming appearance. Remembering the scream, I timidly knocked on the door. Mitchell, thinking it was the replacement manager, whom he had sent to find the correct list, opened the door with a roar. Seeing me, he suddenly, in the middle of a sentence, modulated to a soft, very smooth, “Oh, hello, please do come in.” It turned out to be a fortuitous meeting because by an extraordinary coincidence it turned out I resembled his own son. We began talking, when suddenly there was a knock at the door by the returning manager. Mitchell opened the door, introduced the manager to me saying, “This is Mr &hellip, who has most kindly offered to help us out &hellip,” then his voice rose to an insane, angry level. He began shouting at the manager and actually picked up a chair and threw it against the wall before kicking the man out! Then he turned to me and sweetly said, “Now, where were we?” When I left I knew I did not want to associate with him!

Next, I had an appointment to talk with Eugene Ormandy in Ann Arbor, where the orchestra was giving its annual May Festival concerts. I met him during a break in a rehearsal and my arrival had been preceded by a telephone call from his friend, Louis Wersen, Head of Public School Music in Philadelphia, who had seen me conduct at an MENC conference in Missoula. Before I had finished my carefully rehearsed introduction, Ormandy interrupted me with the question, “Are you talented?” Before I could think how to answer so direct a question, he continued, “What I mean is, there are many people who are good conductors, but only a tiny handful who have real talent.” I responded that some people had expressed that they believed I was such a conductor. With that, he invited me to spend the next season with him, but made it very clear he could promise nothing. I was very excited not only to finally have an option for the following year, but because I had admired him so much as a conductor during my student years at Michigan.

My next appointment was with Sexton Ehrling, then conductor of the Detroit Symphony. He was very open and very friendly and we had a long talk about conducting. I recall he was thinking of ending his career as a conductor, primarily because he was exhausted from memorizing scores week after week. Especially, he said, contemporary scores, which were often too difficult to use a score. He made me a clear offer to be his assistant if I would be willing to prepare all the scores and be ready to replace him at a moment’s notice.

Thus I was presented with a very difficult choice. It was clear that my opportunities to actually conduct were much greater in Detroit. On the other hand, the Detroit orchestra was not in the same class with the Philadelphia and Ehrling, himself, not of the reputation of Ormandy. As it turned out, Ormandy was not the type of person to ever interest himself in another’s career and so, from a career perspective, I probably made the wrong choice. However, I have never regretted this choice, because having the opportunity to hear each rehearsal and concert of the Philadelphia Orchestra for a year proved to be a tremendous learning experience with regard to music itself. In that regard, I have always thought I made the correct choice.

My thoughts on orchestral conducting were further clarified during my final Summer in Missoula when I was asked to conduct an opera, The Bartered Bride, by Smetana. It was a miserable, small pick-up orchestra, but an imported cast of very strong singers, one of whom went on to have a major international career. I studied the score in great detail but soon found that the role of the opera conductor is to follow the singer. He has very little opportunity to shape the performance in the way a conductor normally does. After this experience I knew this branch of the art was not for me.