Guest Appearance

- Guest Speaker, Northwest Division Convention, cbdna, Pullman, Washington

Articles and Monographs

- David Whitwell, “The College Band: Can It Escape Its Heritage?,” Music Educators Journal 51, no. 6 (July 1965): 57, https://doi.org/10.2307/3390457

- David Whitwell, “Beethoven: His Music for Winds,” The Instrumentalist, October 1965.

- David Whitwell, “Schubert: His Music for Winds,” The Instrumentalist, November 1965.

- David Whitwell, “Wagner: His Music for Winds,” The Instrumentalist, December 1965.

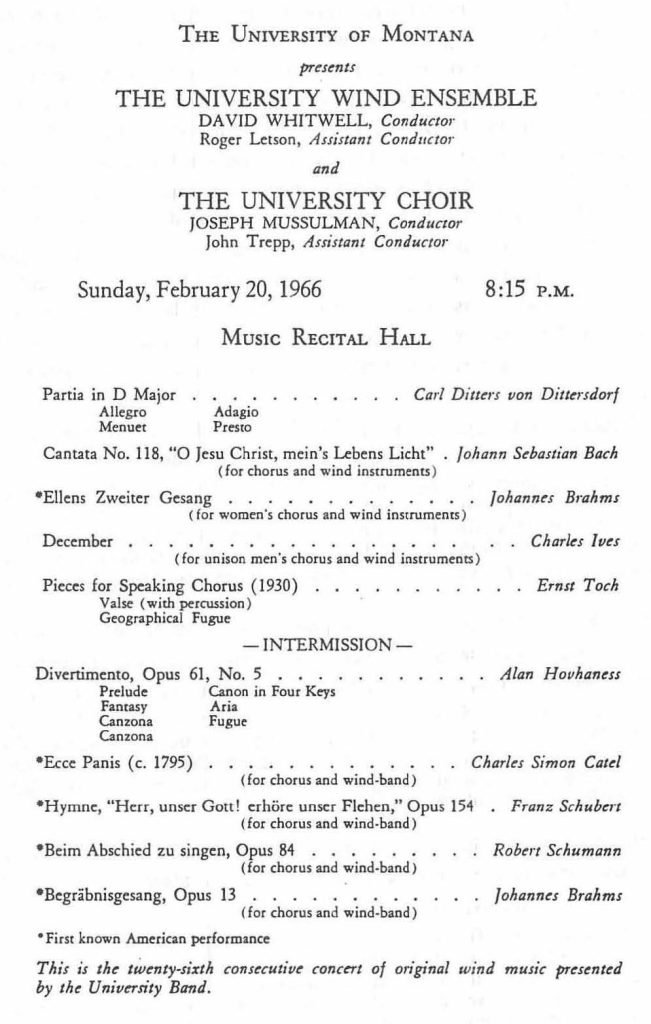

- David Whitwell, “Music for Voices and Mixed Wind Ensembles,” The American Choral Foundation Research Memorandum Nr. 61, December 1965.

- Ernest B. Ryder et al., “A Marching Band Symposium,” Music Educators Journal 52, no. 3 (January 1, 1966): 64–66, https://doi.org/10.2307/3390620

- David Whitwell, “Berlioz: His Music for Winds,” The Instrumentalist, January 1966.

- David Whitwell, “Brahms: His Music for Winds,” The Instrumentalist, February 1966.

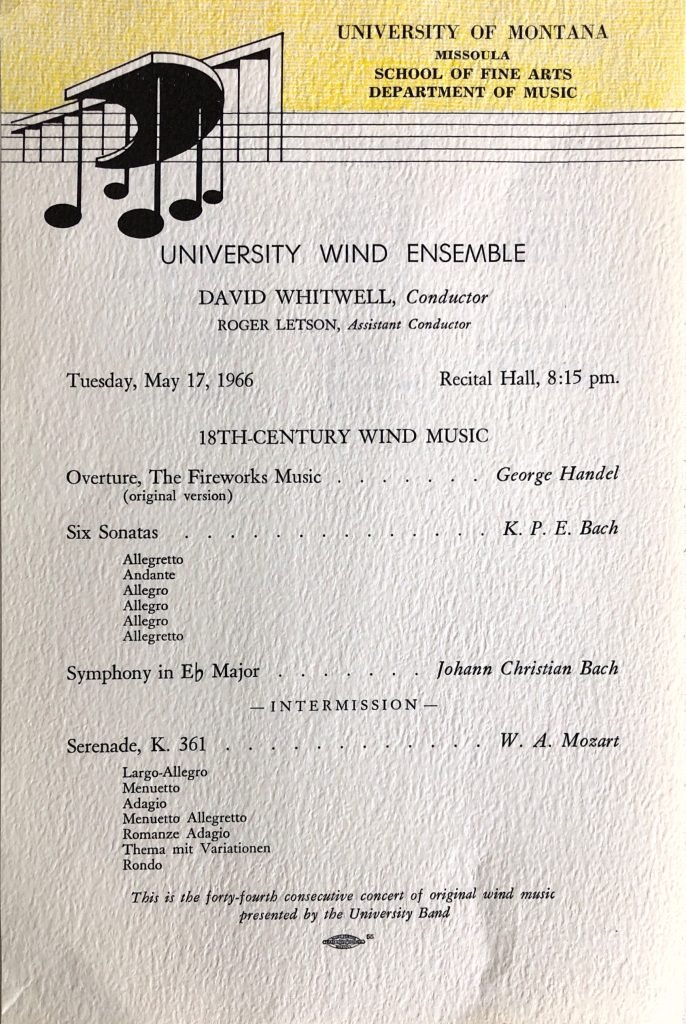

- David Whitwell, “Mozart: His Music for Winds,” March 1966.

- David Whitwell, “Haydn: His Music for Winds,” The Instrumentalist, April 1966.

- David Whitwell, “Strauss: His Music for Winds,” The Instrumentalist, May 1966.

- David Whitwell, “Music for Voices and Woodwind Instruments,” The American Choral Foundation Research Memorandum Nr. 64, May 1966.

- David Whitwell, “Stravinsky: His Music for Winds,” The Instrumentalist, June 1966.

Recordings

University of Montana Band, Highlights of the 1965–66 Season, Dr David Whitwell, Conductor

1. Vincent Persichetti, Symphony No. 6

2. Vaclav Nelhybel, Prelude and Fugue

3. Jan Meyerowitz, Three Comments on War

4. Vaclav Nelhybel, Trittico (Vaclav Nelhybel conducting)

This academic year began with a change of name for the institution, which was henceforth known as the University of Montana. The sister institution at Bozeman took our old name, Montana State University.

During the football season of 1965 I continued to base the shows around geometric drill routines, which, although rather simple to execute, always amazed the viewers. The football crowd was especially impressed with a new tradition I began this year by which we would form in numbers on the field the half-time score, whatever it was. This meant that each student had to memorize ten possible routines and on those occasions when a touchdown was scored in the final seconds some students had to adjust their thinking very quickly. The audience, of course, always wondered how we knew in advance what the score would be, as they supposed we had been rehearsing all week! In fact, at one point I was visited by two shady-looking charcters from Las Vegas, wanting to pay me for revealing in advance what the half-time score would be! Our annual Band Day, in which hundreds of student musicians would perform together, always seemed to be of great interest to the public. The Missoula newspaper this year commented,

We can’t say too much about the halftime spectacular put on by the University of Montana Treasure State Band and the 10 high school bands.

We believe this show, with some 750 musicians participating, equaled any halftime show anywhere in the nation.

The ones we’ve been privileged to see and hear have been accomplished with precision and great coordination. We’d have to say it’s a miracle of modern education and know-how when you consider these 11 musical organizations had only a brief rehearsal to prepare the polished performance they gave.

Congratulations to Dr David Whitwell of the University, his staff, and the directors of the participating bands—a tremendous task carried off impressively!

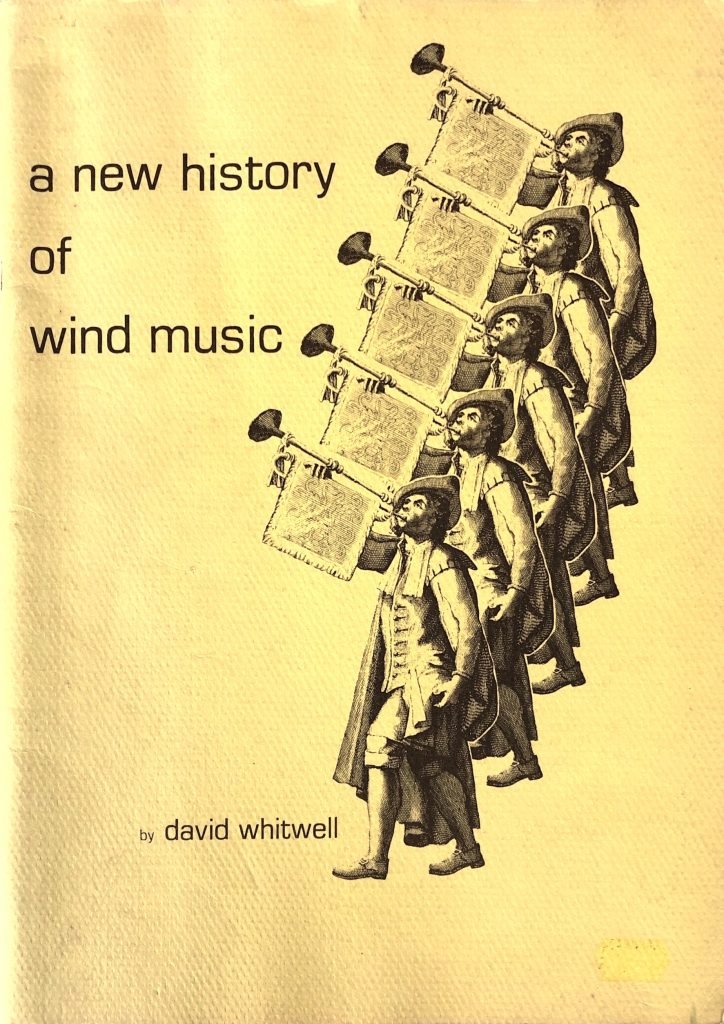

During the previous Summer, while camping in Yellowstone National Park, I had the idea to write an article on the band music of Beethoven. This resulted in a series of articles on the band music of various composers, nine of which were published by The Instrumentalist this year resulting with welcome additional income. The series would continue for several years and the material would eventually be republished as my first book, A New History of Wind Music.1

The Instrumentalist, under the name of a separate publishing company they maintained called The M-F Company, also began a series of my editions of early original wind music. These editions included works by Brahms, Bach, Catel, and Berger. In view of all this activity I was also asked to become a member of their Board of Advisors.

The previous December I was elected Vice-President of the Northwest Division of CBDNA. During the current Fall the person whom had been elected President left the profession and so I became President. This included membership in the national board of directors and so I attended the meeting of this group in Chicago in December 1965. To help college band directors become aware of earlier wind band music, I proposed the establishment of a new standing committee on “Historical Band Music.” The national president, a Californian who was an early advocate of introducing jazz in the school programs, denied this request. When this was followed by his establishment of a national jazz committee, it was, for me, a dismal harbinger of the future of the college band.

The concert band was even better this year and its growing maturity allowed us to perform major wind band compositions. On our Spring concert tour, to eleven Montana towns and Sheridan, Wyoming, and Williston, North Dakota, our repertoire included the Persichetti Symphony and a new manuscript work, the Three Comments on War by Jan Meyerowitz. I sent the latter composer a recording of one of our performances and he responded,

It is absolutely marvelous. All of it. Your band is most excellent. But it is your superior, vibrant musicianship and expressive personality that gives the exceptional pleasure in this performance. I wished I wouldn’t have to limit myself to written words—it always seems to me that all words are alike. It’s a great pity that you are so far away.

For the students and myself one of the highlights of the Spring concert season was the visit to the campus of the composer Vaclav Nelhybel. His music at this time was bringing an entirely new Eastern European style to the national band repertoire and having him conduct this new sounding music was a great thrill for the students.

The composer wrote,

I was enchanted with the reaction of your musicians. It was a pleasure to work with them. Your band is a sensitive musical instrument with an enormous range of communicative power …

Please tell Hello to all the members of the band and tell them that I loved to work with them and that I was very happy with the results. I was touched by their friendliness—despite my tough rehearsing. I knew that they were able to give me all the subtle details—thus I tried to get them.

Giselle was working on her Masters Degree in the Spanish Department at the university and doing some teaching for them as well. Since the public schools in Missoula offered no foreign languages at this time, she had made a proposal to the local school board to begin a foreign language program after school. She proposed to offer German and Spanish to students at $2.50 per hour, but it was denied by the board. They had no policy for after school use of the facilities and their concern, according to the local newspaper, was that, “permission for Mrs Whitwell would encourage a host of similar requests to teach everything from foreign languages to guitar playing in the schools.”

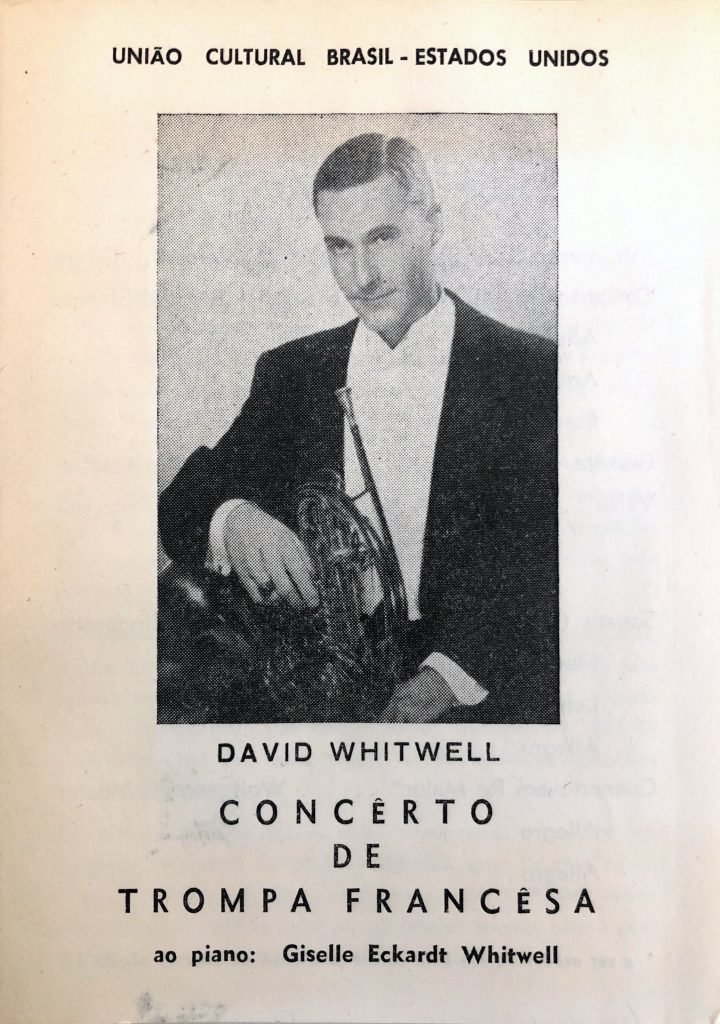

Since our marriage we had had many expressions of interest from Giselle’s relatives in Bolivia in our visiting in order that they could meet her new husband. We decided we should make this visit in the Summer of 1966 and in order to make the trip tax deductible we decided to make it a recital tour of South America. Accordingly I wrote to all the embassies in major cities offering to perform. For a long period we received no answers and then suddenly letters of acceptance began to arrive. It turned out that the individual embassies could not act without the State Department’s approval, something, had we known, we should have done initially. The State Department had its Music Advisory Committee check us out with their contacts in the United States and subsequently they awarded us with their highest possible artistic rating. This, in turn, opened all the doors and in many cities we received substantial financial help, not to mention invaluable services in transporting us around and arranging for us to meet important persons in each city. With the State Department handling the tour, all aspects of the performance halls, publicity, and accommodations were superb.

We began our tour in Lima, Peru, where we were met by an official of the Peruvian–North America Cultural Institute who immediately drove us to a luncheon in our honor attended by a number of the leading musicians in Lima. The following day, a chamber wind ensemble, consisting of members of the National Orchestra of Peru invited me to conduct a two-hour rehearsal of the Dvorak Serenade2 and the Mozart Partita, K. 384a. All of these young musicians, as was often the case in South American orchestras, were European. In our social meetings with them we heard lively debates regarding the musical preparation they had had in their native countries. The Italians, for example, felt that they had not had sufficient training in “practical” matters, such as theory, history, and technical training on their instruments, but felt whatever they lacked in this respect was more than made up by their unequaled concept of tonal beauty!

We encountered here, as we were to find in every country, very little knowledge of musical activities in the United States. Sometimes musicians would pretend to be surprised that there were orchestras in the United States. I also got to know the conductor of the National Orchestra, Sr Leopoldo La Rosa, who invited me to guest conduct if we returned.

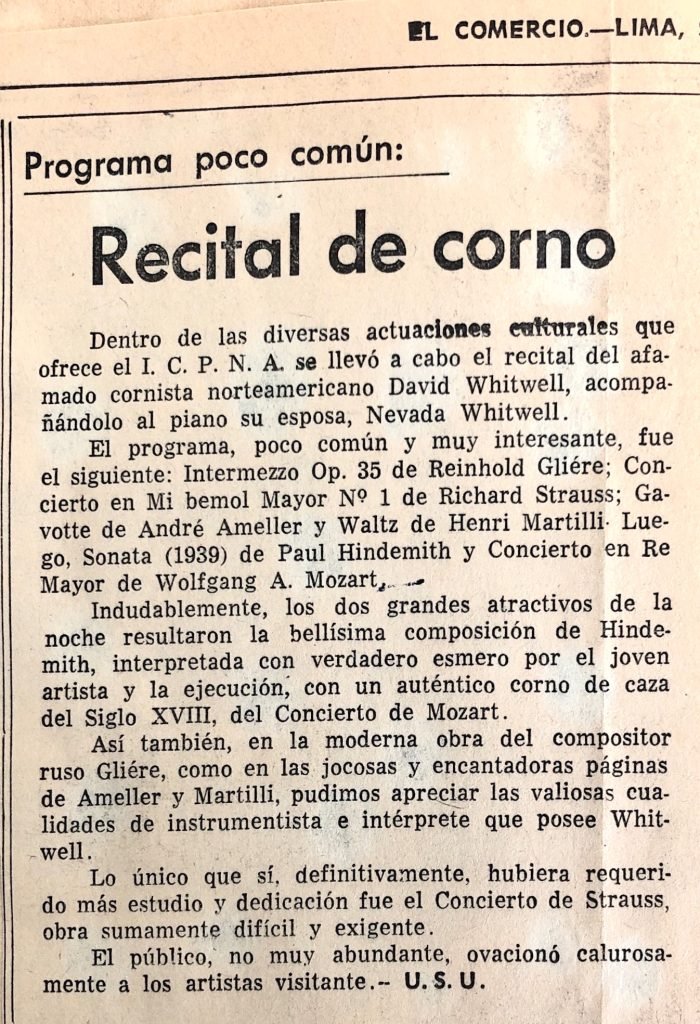

The reviews from Lima included the following from the El Comercio, 30 July 1966.

Undoubtedly, the two great attractions of the evening were the beautiful composition by Hindemith, interpreted with true eminence by the young artist, and the execution of the Mozart Concerto on an authentic 18th century hunting horn. We appreciate the valuable qualities as interpreter that Whitwell possesses.

Our next stop was Giselle’s home for ten years, La Paz, Bolivia. Because of the great altitude (the city is at 13,000 feet!), it always takes visitors a week to feel healthy, therefore we scheduled no concerts for the first week. We did, however, have numerous social commitments, in fact eighteen in the first nine days. One of these was a memorable party given for us by the Vice President of Bolivia attended by Bolivian cabinet members as well as the United States Ambassador, Douglas Henderson.

Our first appearance was a live national radio broadcast over Radio Mendez. In a tradition long lost in the United States, there was also a live audience of more than three hundred people in the station.

The first formal recital in La Paz was before an invited group of ambassadors and their wives held in a very large room in the home of Ambassador Henderson. We had been asked by Mrs Henderson several times to come by to check the tuning of the piano, but, not wanting to bother her, we assured her not to worry. In one of these calls she pointed out that there was only one piano tuner in La Paz and he was “on strike” against the United States! When we arrived we found that the evening was to begin with a formal dinner in our honor, which included numerous toasts. Since it always required my complete presence of mind to be a reasonably good horn player, I had always had the rule of never drinking before playing. Therefore, I was growing increasingly alarmed as I was required to respond to toast after toast.

When it was time to play, to my horror I found that the piano was more than a whole-step lower than the standard 440, lower than my tuning slide could accommodate. With a room full of ambassadors one could not, of course, turn around and say, “I’m sorry, we can’t perform.” Therefore, the only alternative was for me to transpose the recital, Hindemith and all! This was a particular problem with the Mozart D Major Concerto, which I had intended to play on an authentic eighteenth-century natural horn in D. Since it could not be tuned at all, I had to use my regular horn, thinking of the score in C, transposed to F, and then down to D concert. Due no doubt to the quantity of wine I had consumed in the toasts, I was very relaxed and somehow did all of this. The odd thing, however, was that, though sitting and playing, I had the mental impression that I was only listening while some other part of my brain was actually doing the playing! The following day, however, I had a major case of cold chills!

Another interesting concert in Bolivia was with the National Orchestra of Bolivia, in Mozart’s Concerto, K. 495. The discipline of this orchestra was the worst I had ever observed. The rehearsal was called for 7:00 pm, but the musicians only arrived by about 7:40 pm and the rehearsal finally began at 8:00 pm. During the dress rehearsal of a Beethoven Symphony on the program one horn player got mad, rose, tore up his part, and flinging it into the air like so much confetti, walked out!

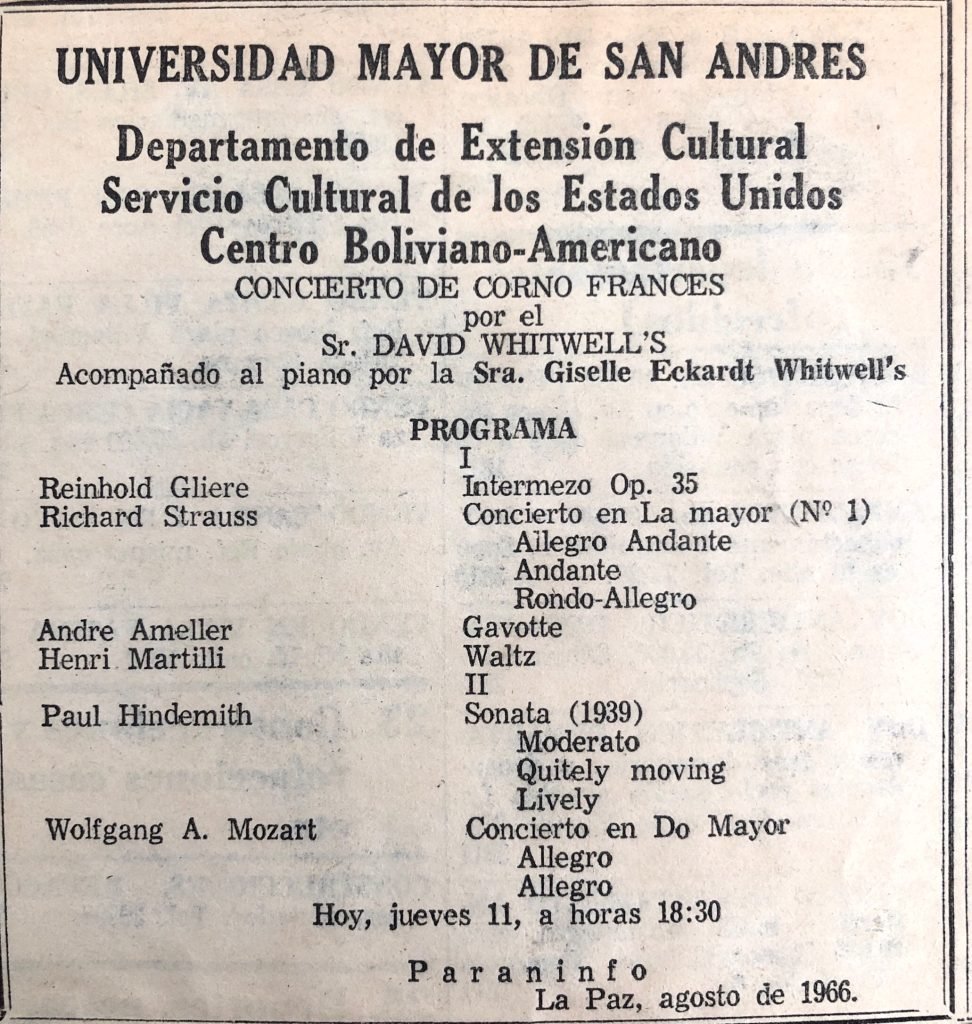

Our official public recital in La Paz was at the Universidad Mayor de San Andres (see fig. 28), where we were again honored by the attendance of Ambassador and Mrs Henderson, who postponed a previous engagement in order to hear us again. On our departure they gave us a valuable antique silver chalice. The press wrote,

One can affirm that this concerto (Mozart, k. 495 with orchestra) communicated a true aesthetic emotion. Whitwell interpreted Mozart with a fine sobriety and a profound message.

El Diario (11 August 1966)

Professor Whitwell demonstrated brilliant virtues of interpretation and the technical handling of his instrument was very exact. The public gave their affirmative testimony with a prolonged ovation.

Ultima Hora (11 August 1966)

Omitting the unnecessary analysis of this great virtuoso’s program, one can affirm that this meaningful concert, by its transcendent sobriety, revealed the end that this difficult path of art pursues. The Gliere was developed with a beautiful interpretation of subtle effects. The vital qualities in the Strauss and Hindemith were warmth and brilliance. This fine recital has inspired in our musical circle a new orientation in favor of great contemporary music. The magnificence of the interpreters was projected in a sense of emotional economy, yet with a vigorous demonstration of the absolute factor in the music of our times.

El Diario (12 August 1966)

In Santiago, Chile, we heard two of the better professional orchestras in Latin America, with strings truly first-rate by any standard. In addition to a performance at the National Conservatory of Music, we were sent to the beautiful seaport of Antofagasta for a recital at the University of the North. The sea and a very enthusiastic audience combined to make this a most enjoyable visit.

Our flight from La Paz to Antofagasta was a very interesting experience. The only commercial jet owned at this time by Chile had been taken over by the country’s President. Therefore our flight was on the civilian equivalent of the DC-6, which I had flown in so much in the Air Force. As I knew from this experience that the ceiling of the DC-6 was supposed to be 11,000 feet, I was rather concerned as I boarded the plane at the La Paz airport where it was already 14,000 feet on the ground! Sure enough, we took off and flew only about thirty feet over the ground for many miles, until the ground eventually began to fall below us as we neared the sea. For about an hour it was like looking out the window of a bus!

For any musician a visit to Buenos Aires is always exciting. Nearly the size of New York, it is the leading center of music in South America. In addition the food was great and I doubt if any menu in town had prices over $4.00 for a full meal. The week before our arrival there was a coup and we assumed the concerts would be canceled. However, we immediately received a cable from the Embassy assuring us that life goes on in Argentina regardless of who is running the government.

Please don’t let the recent “coup” cause you to change your planned visit to Argentina. Although diplomatic relations have been suspended, there has been no violence and the busy musical life here is going on as usual.

Of our two concerts in Buenos Aires, the most interesting was a recital at the Catholic University of Argentina. Upon our arrival I noticed that the posters announced a formal lecture in addition to the recital. Needless to say, this was only one of many occasions when our success depended on Giselle’s native Spanish. There was in Buenos Aires at this time a concert band made up of blind musicians and the entire horn section attended this concert. I was very moved when they came up afterward and said, “We want to meet the Master.” More interesting was their eagerness to feel, or as they said, “to see,” the natural horn—an instrument never before heard in South America. When I allowed each of them to play a few notes on the instrument they were the happiest men alive. The Buenos Aires Prensa (27 August 1966) wrote, “Beautiful sonorities, put at the service of a true musical temperament.”

While in Buenos Aires, I commissioned Roberto Caamaño, one of South America’s leading composers, to write a work for band, which we could play at the National Convention of the CBDNA in Ann Arbor, in 1967.

Our next recital was in Sao Paulo, Brazil, a beautiful modern city larger than Chicago. Our recital here had some problems due to a nearly blind page turner and a photographer who walked around the stage, flash and all. While in Sao Paulo I had an offer to return the following season as guest conductor of the orchestra.

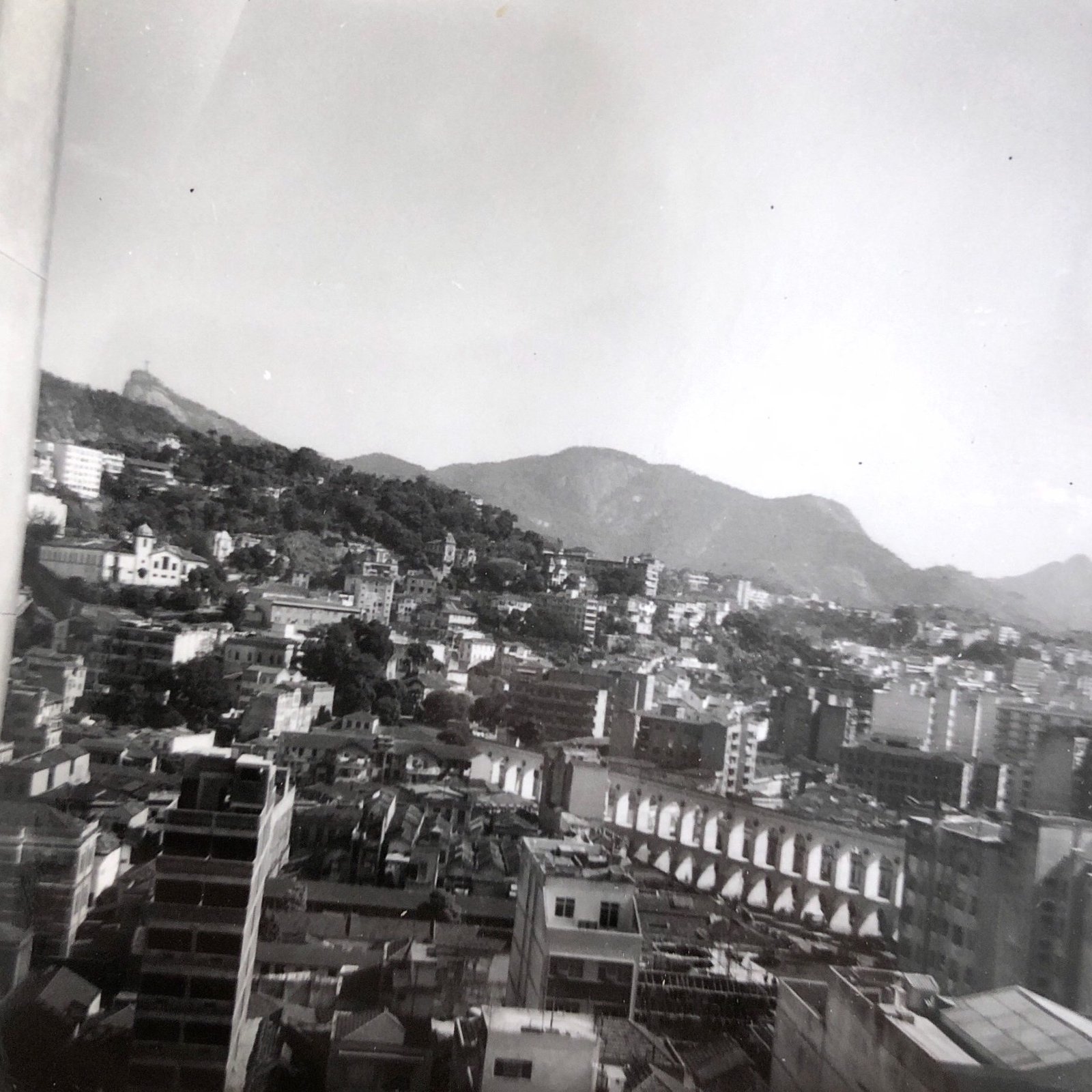

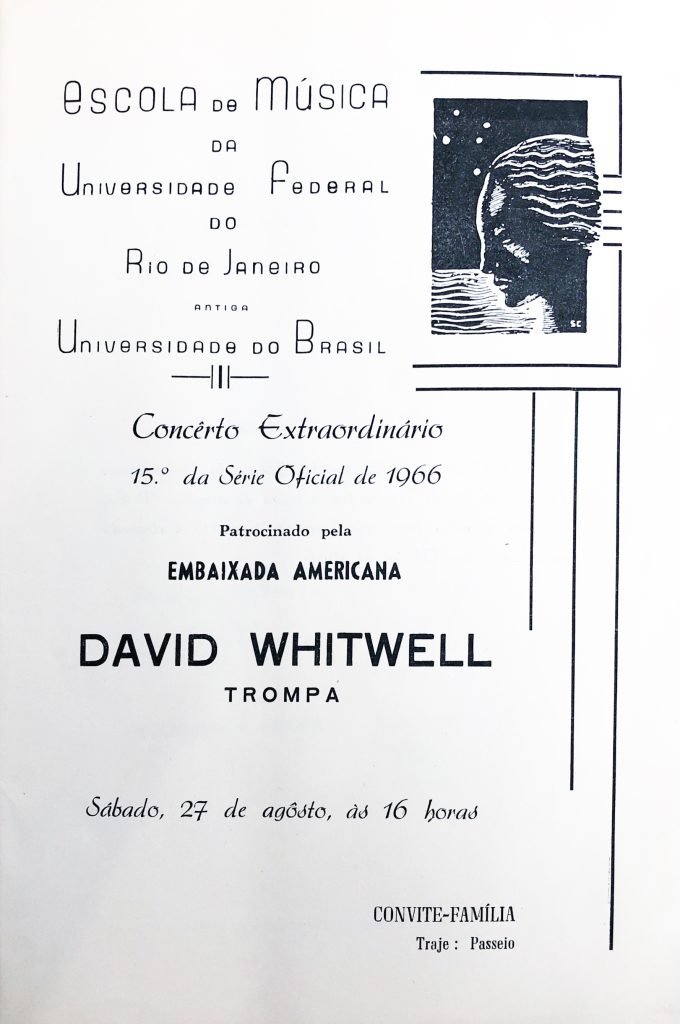

This was followed by a concert in Rio de Janeiro in the beautiful auditorium of the National School of Music, where we had a very enthusiastic audience. The National School of Music offered me a contract as Professor of Horn, an offer difficult to turn down given this unbelievably beautiful city. The Rio de Janeiro O Globo (31 August 1966) wrote, “The Strauss impressed us very much. Whitwell has demonstrated throughout a complete control.”

The following concert had been scheduled in Brasilia, a very formal recital with personal invitations mailed to each member of the World Apartheid Conference then in session. The unannounced elimination of a Varig flight and the resultant danger of missing our Caracas and Mexico City concerts forced us to cancel this concert the day before, to the great disappointment of the State Department.

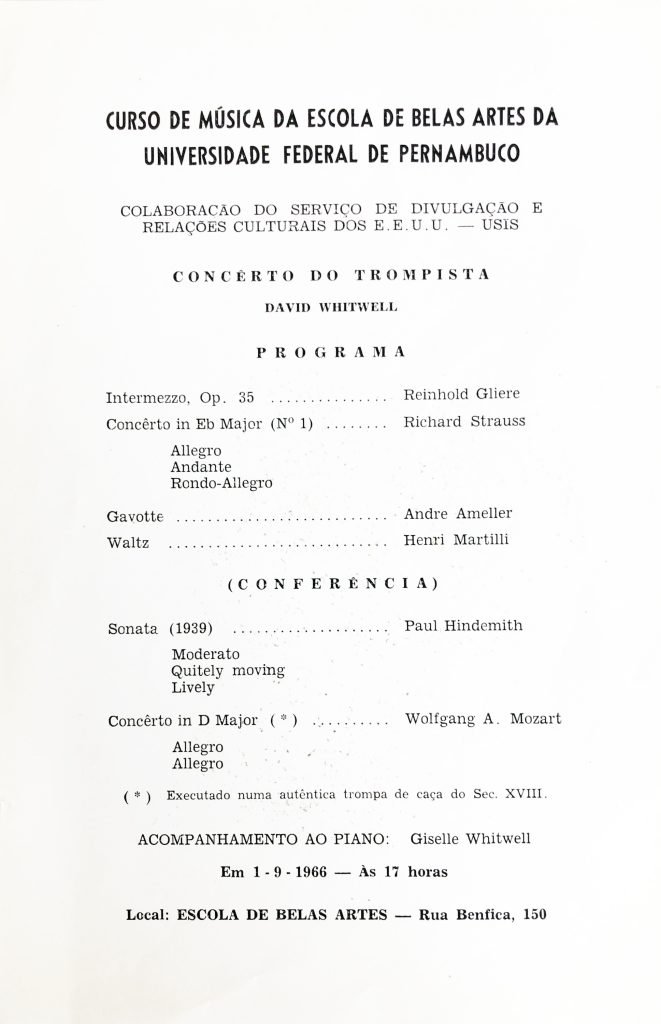

Our next recital was, therefore, in the School of Fine Arts of the Federal University of Pernambuco in Recife. Having been in winter climate, we were suddenly now in the tropics. The hot temperature, of course, made both horns quite sharp and consequently on the natural horn I was able to make almost no distinction between natural and “muted” tones. A personal highlight was visiting with Giselle’s brother who was in college here. Giselle had not seen him since he was twelve and now he was not only married but had the birth of his first child the day we arrived. For our flight to Caracas it was necessary to return for a day to Rio de Janeiro, where the State Department arranged for me to spend a day with Mrs Villa-Lobos. Like her late husband, she spoke only French with visitors and so we had to suddenly recall all the French we could. She showed us many of the composer’s manuscripts and personal effects and gave us five recordings of his music as a gift.

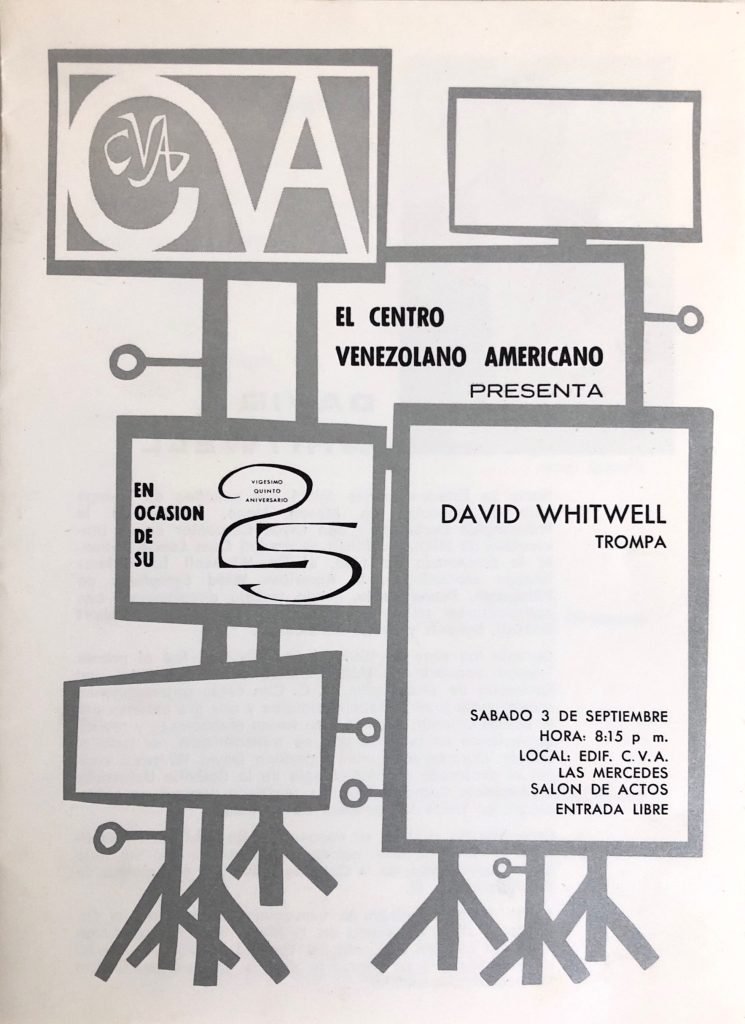

We had a very successful concert in Caracas, Venezuela, and the El Mundo (14 September 1966) wrote,

… an extraordinary, delightful concert &hellip it is his professional work as an artist, as an interpreter, that we have appreciated greatly on this musical evening. Whitwell demonstrated to the numerous audience his quality as an instrumentalist, his sure technique, and a profoundly cultivated musical sensibility.

The quality of his sound is always of great purity and his artistic temperament gives evidence of eminence. It is from this that his interpretations result. The excellent version of the Hindemith Sonata and the Mozart Concerto earned the most warm applause of the numerous listeners who went with great curiosity to hear this extraordinary horn player, which he without doubt is.

Our final recital was in Mexico City in the Instituto Mexicano Norte-Americano de Relaciones Culturales, where we had a large and warm audience—and the best piano of the trip. We were guests at a lavish reception and a member of the government asked us to extend our stay and make a concert tour giving ninety-five concerts throughout the country at their expense. After seven weeks on the road we were too tired to accept this interesting proposal, not to mention the fact that it was nearly time to return to Missoula for the Fall Quarter.

The critics in Mexico City wrote,

The North American hornist, Whitwell, had much success in this the first such presentation in our country. Whitwell gives a personal accent and a perfect interpretation of the scores &hellip After the concert a reception was offered, during which the visiting artists received innumerable congratulations by those who know how to appreciate good music and its worthy interpreters.

Novedades (12 September 1966)

The distinguished hornist, David Whitwell, offered a brilliant concert &hellip a magnificent recital.”

Universal (12 September 1966)

We returned to Missoula, filled with incredible stories and, due to countless newspaper articles and reviews, feeling like international celebrities. We found no one among the music faculty was particularly interested in hearing about our experiences; it was as if we had only made a tour of Eastern Montana. We took this surprising disinterest as a result of too many years of isolation and it was the occasion for our first thoughts that we should begin to think of leaving the university before we became like all of them.

During this year I was invited to speak before the Northwest Division of the CBDNA, which met in Pullman, Washington. I gave a major address, twenty-one pages long in print, in which I reviewed the state of the band’s repertoire, our lack of knowledge of older original band repertoire, and a number of aesthetic questions, in particular, how our bands function before the public. In part, I said,

It seems odd that by this date an adequate history of wind music has never been written. It is true that a handful of works regarding this history of bands have appeared. But these have only contributed to the isolation of our medium, for they fail to substantiate wind music’s role in music history in general. In truth, the adequate history of wind music will not be written for some years. There are far too many important gaps that must be filled first.

I am not sure what impact this long, passionate address had on this small gathering in Pullman, but it seems clear in retrospect that the preparation of it was the seed from which my later research and publication would grow. The final result of my interest in this history would come between 1980 and 1992, when I published my twelve-volume History and Literature of the Wind Band and Wind Ensemble.