Articles and Monographs

- David Whitwell, “Music for Voices and Brass Ensemble,” The American Choral Foundation Research Memorandum Nr. 53, December 1964.

- David Whitwell, “Band Conductors Born in 1965: What Will be Their Heritage?,” Cadenza, January 1965.

- David Whitwell, “What’s Missing?—Proper Approach to Style,” The School Musician, January 1965.

- David Whitwell, “Attitude Toward the Marching Band,” The Instrumentalist, February 1965.

- David Whitwell, “Three Crises in Band Repertoire,” The Instrumentalist, March 1965.

- David Whitwell, “On the Repertory for Chorus and Band,” American Choral Review, March 1965.

- David Whitwell, “Music for Voices and Trumpets, Horns, or Trombones,” The American Choral Foundation Research Memorandum Nr. 56, April 1965.

Recordings

University of Montana Band, Highlights of the 1964–65 Season, Dr David Whitwell, Conductor

1. Vittorio Giannini, Symphony for Band

2. Leroy Anderson, A Trumpeter’s Lullaby, Doc Severinsen, soloist

3. Charles Carter, Symphonic Overture

4. Gordon Jacob, Music for a Festival

5. Morton Gould, Jericho

6. John Philip Sousa, Manhattan Beach March

I was very fortunate that my second year of teaching began with the arrival of two older and very experienced doctoral students, William E. Gamble and Ralph Downey, who gave me an unending supply of valuable advice. Their immediate impact was in convincing me to go to a drill style marching band, rather than the old stick-figure style. For a low stadium, such as ours, this made for a much more interesting field show and it also allowed us to perform more interesting music.

With my two new graduate students helping the general quality of the marching band was much higher. For the first time I received very nice notes from the President and faculty. The wife of the athletic director wrote, “the band was magnificent last Saturday. Congratulations! You make us proud of you.” A member of the public wrote,

Is it too late to congratulate you and your band members on a wonderful and memorable season for the football fans? The half-time performances were all great, but especially the Bobcat game. The band music adds so much to the games. I’m always sorry the people in the stands show so little appreciation. Again, thank you and congratulations!

This lady’s comment about the audience hits the mark on one of the great truths unknown to marching band directors—no one pays attention. It is a time to talk with friends, go get beer and go to the restrooms.

Because the length of the game’s half-time is limited by contract between the schools playing, the band’s show, together with any other activities, must be precisely planned. For the purpose of maintaining the necessary control of half-time activities the athletic department put me in charge of this time and anyone who wanted to participate had to make their plans with me in advance in order that I could tailor the length of the band show accordingly. For the Homecoming game I had organized our annual “Band Day” and expected to have on the field not only the university band but eight hundred high school musicians as well. Two days before the game I was approached by a representative of the student skydivers team with a request to have twelve skydivers land in the center of the field during half-time. Of course I could not risk the possible injury to one of the eight hundred visiting students so I denied the request. As a result I was attacked in the school newspaper in a letter to the editor by the Vice President of the Skydivers.

This skydiver set forth with love, beauty and happiness in his heart to make the arrangements for the traditional jump. But in trying to make these arrangements he was confronted by two men: Mr Whitwell, head of the University band, a self-absorbed man with a legal mind and no poetry in his thoughts, and Wally Schwank, the fire and brawn director of the athletic department. These two men did not want the students of the University to watch the skydivers. Mr Whitwell wanted the students to watch the band and Wally Schwank wanted the students to watch the football team. Siding with these two people, President Johns stated that the skydivers would be expelled from school if they jumped while the band was playing or during the game …

Crestfallen and in melancholy spirits the 12 skydivers sat on the cold bleacher seats at the Homecoming game and watched with detached gazes as the University band marched and played at half-time.

In the following issue the Co-Chairman of the Homecoming Committee came to my defense.

I feel extremely sorry for Dave Pierce, vice president of the MSU skydivers, and for the rest of those poor, disappointed individuals who were not permitted to jump at the Homecoming game … What a pitiful injustice!

Most of all, I feel sorry for Dave Pierce because he is no better informed than to call Mr Whitwell a “self-absorbed man with a legal mind and no poetry in his heart.” Mr Whitwell worked very hard in order to make this year’s Homecoming a success. He is an unselfish man devoted to his work. Can anyone blame him for not wanting the crowd to gaze skyward, ignoring his carefully arranged halftime performance? I think not …

Had Mr Whitwell been able to work them into his schedule, I am sure that the skydivers would have been permitted to perform. As it is, they will have to seek their glory elsewhere. I have one suggestion: Why don’t they go jump in … oh well, never mind.

The actual half-time presentation was a big hit with the spectators and the local civic newspaper commented,

You’ve got to express admiration for those responsible for the halftime show. Imagine taking 10 bands—one college, eight high school, one grade school—and trying the tricky arrangements of The Stars and Stripes Forever that were heard on Dornblaser Field.

The nearly 800 talented young musicians handled the difficult assignment well, reflecting great credit on the directors of these fine bands. Spanish, Egyptian, Russian and Chinese interpretations were given John Philip Sousa’s masterpiece, before they really cut loose with the stirring march as we know it.

After I had been appointed Director of Bands in the previous Spring I made one of my first priorities replacing the old and unattractive band uniforms which had served the program since 1946. I had several students put on some of the more ragged uniforms which had patches on the seats of the pants and took them to the president’s office. Without a word of introduction, I had the students bend over and present their rear ends to the president. Within a few days the president and the dean of the school of fine arts had worked out a plan whereby a local music store would loan us the money for new uniforms. I designed a uniform which was virtually a set of tails, with a colorful overlay for the field use. They added a great deal to this Fall season.

In the academic year 1963–1964, I conducted my very first full concert before the public. During the rehearsals for this concert, I followed the only model I had observed as a student, the goal of a perfect reproduction of the score achieved by the most continuous stop and go, fix this, fix that, with a fast pace and with eyes glued to the score. I did not give the impression of being angry all the time, as did my mentor, Revelli, but I certainly was in earnest. During one rehearsal one of my colleagues at the University of Montana, Dr Lloyd Oakland, a widely known music educator with an extensive background in university conducting, came to observe my work. When the rehearsal was over, we visited briefly. He stood there, this calm and kindly man, holding his pipe in his hand, smiled and said something like, “My, you are certainly working hard!” I responded, “Yes sir, a rehearsal is the place to work, in order that later you can enjoy listening to the concert!” With eyes twinkling he said, “Well, when I was a conductor I also enjoyed the rehearsal, because it is still music-making!” This comment changed my career as a conductor and in the next rehearsal I was a completely different kind of conductor.

Thinking about his comment over the weekend, I had realized that I had never before been in a band rehearsal as a player where the object was music-making. As a player, I already considered myself as a good musician, but in rehearsal my mind had been drawn elsewhere. When I returned home after playing a university band concert I carried no residual feelings of the joy of music-making, my only awareness was, “How did I play? Did I miss any notes, attacks, rhythms, etc.? Did anyone in the audience notice my playing?” It is exactly what clinical research found in the early days of discussion of our bicameral brain. The listener, having no score and using only the ears, hears music mainly with the left ear (right brain), focusing on the experiential aspects of the music, especially the emotional communication. The musician, they found, listens mainly with the right ear (left brain), to the rational, data aspects of music, due to the nature of how we teach music. One scientist observed that the result of the study of music was to ruin the person as a listener.

There is a serious misconception here, caused because the conductor has forgotten that music is for the ear, not the eye. The truth is that there is no music on that score page, only the grammar of music. And so when the conductor is standing there, bent over the score using his eyes to watch for things to be fixed, his entire attention is focused on the page, the data information exclusive to the left brain. Because these two brains work separately and do not work together in tandem, music does not have a chance. His goal is wrong.

The goal is not to reproduce that page, but to reproduce the music the page represents.

Music is very ancient, dating to the period when man lived in caves. How much have we lost when music began to be written down, as something to be read?

This Fall also saw the arrival of a large group of talented and serious new freshmen. With their fresh influence the concert band was immediately far better than the previous year. A professor of psychology wrote to the president of the university,

As a newcomer to the faculty I want to express a note of appreciation for the fine musical concerts we have been hearing on this campus. The performance of the concert band last night was outstanding.

I was particularly impressed with the interesting choice of program, the creative conducting of Dr Whitwell, and the finesse and dash of the entire ensemble. They are a credit to the University and I hope we will hear more of such presentations.

After another concert, with one of music for band and chorus, the Chairman of the Department thought my work with the choir was “very fine. Did you ever consider choral conducting?”

By the time we made an extended tour throughout Western Montana and Canada in March they were really a first-rate university band. The concerts they gave on this tour made a tremendous impression in each city and resulted in numerous letters of praise. Roger Heath, the band director at Great Falls High School, who would later go on to become the assistant director at Purdue University, wrote,

The extraordinary performance of the Montana University Band in Great Falls last March certainly impressed us with the caliber of work being done in band at the University. Dr Whitwell’s demands to meet the highest musical standards in performance are self-evident, and the pride in accomplishment is obviously reflected in the attitude of the members. The near perfection in the area of tone colors, the exciting conducting and the group’s remarkable technical facility made this appearance a striking contrast to the average college band performance.

Mr Orlon Strom, of Cardston, Canada, wrote,

Merely to say that the concert was a success would be an understatement. Even though thoroughly enjoyable to the audience, the values of this appearance went beyond pleasurable listening—intellectual worth for example. The choice of music, including the contemporary works, showed fine taste, this was surpassed only by the interpretation and musicianship which definitely proved the band to be an exceptional group under the leadership of an inspiring and very able conductor.

Mr Cyril Mossop, Supervisor of Music, Calgary, Canada:

To say that the students and teachers were impressed is an understatement. The performances by this excellent group were of a very high caliber; the technically difficult sections came off with commendable precision. The band under the artistic direction of Mr Whitwell displayed an exceptionally wide range of dynamics with secure intonation and excellent blend at all times. To sum up, it was a “top” performance.

Mr L. E. Hetrick, a high school conductor from Whitefish, Montana:

It was our pleasure to host in concert such a group of selected college musicians whose talents have been superbly drawn out by you, Dr Whitwell, and molded into musical performance of the finest caliber … Our students found much to emulate and the impressions were lasting.

Mr Don Lawrence, a high school conductor from Columbia Falls, Montana:

The entire student body of Columbia Falls High School was very much impressed with the concert. Never before or since has such whole-hearted enthusiasm been displayed for a musical performance in our school.

Mrs J. A. Cameaux [a parent], Spokane, Washington:

Thank you, thank you for the wonderful band trip you gave Nan! And for being the person who brought forth the comment—“There’s one person I really respect—and that’s Dr Whitwell.” She can’t abide wishy-washy people and she has very admirable comments on your behalf.

Mr C. I. Carlson, high school conductor of Havre, Montana:

I have worked in Montana for many years and have heard the University Band each year in concert. This is the most outstanding University band that I have heard. The tone, the precision of the band and the fine interpretation given by its very capable director qualifies this organization as one of the top bands in our country.

Mr Paul Nelson, high school conductor of Big Timber, Montana:

I cannot over-stress how valuable and important these concert tours are to those of us teaching in outlying areas. They represent a tremendous service to the cause of music in the state as well as to the individual schools visited. No music student can achieve beyond his own level of experience. We consider ourselves extremely fortunate to have such a professional quality group perform for our students.

Mr Gary Thune, Glendive, Montana:

The band concert you and your fine band performed at Dawson County High School was the finest I have ever heard from any band. It was very inspiring for me to observe the professionalism of you and your associate director, as well as the discipline of the artists you conduct. Thank you very much for a truly remarkable and memorable experience.

Mr Ray Sims, high school conductor of Butte, Montana:

Never before has a musical organization set a more shining example for a group of high school students. The band’s interpretation and musical style were definitely outstanding.

Mr Ernest Hagen, Billings, Montana:

It is, I think, the best band I have ever heard and surely one of the great bands in America.

I was determined this year to continue my crusade to influence my profession toward the performance of original band repertoire rather than a repertoire of primarily transcribed orchestral works. Leaving aside the fact that there was plenty of good original wind music which could and should be performed, my principal objections were in the performance of the transcriptions of mere excerpts of orchestral works and in the performance of minor works which even the orchestras of the day did not play. It was the latter I think, in retrospect, which was at the root of my prejudice at this time, for in previous years as a player I had played some rather poor music which had become part of the national repertoire simply because it was published. In later years I came to see that there are some transcriptions which are very effective in the wind band medium and are rewarding to perform. At this time, however, it seemed to me that to give my arguments an ethical foundation I should just not play them at all. Therefore in this year I began to perform only original wind music.

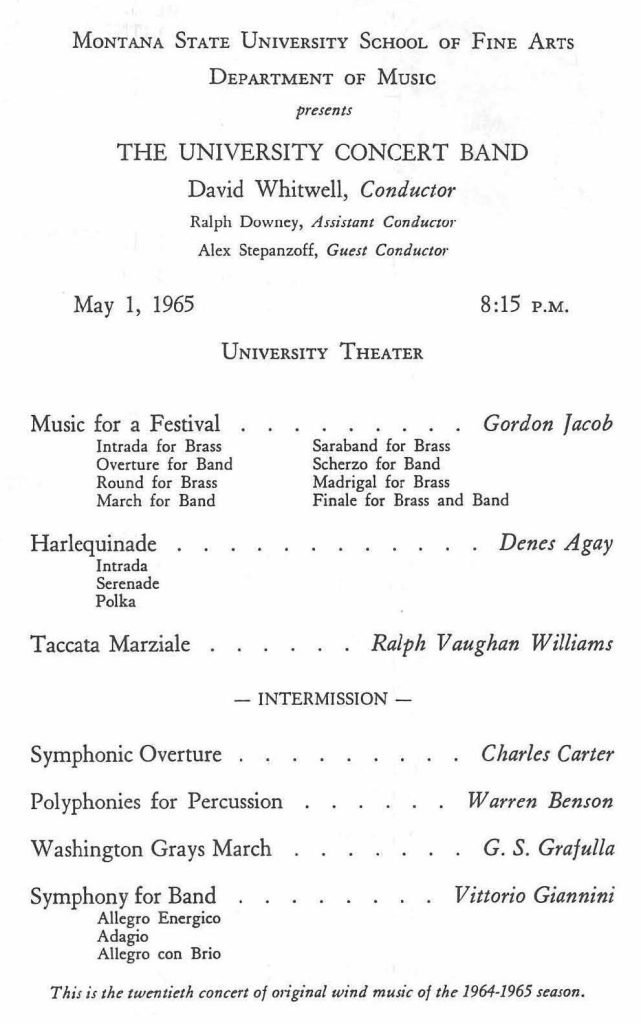

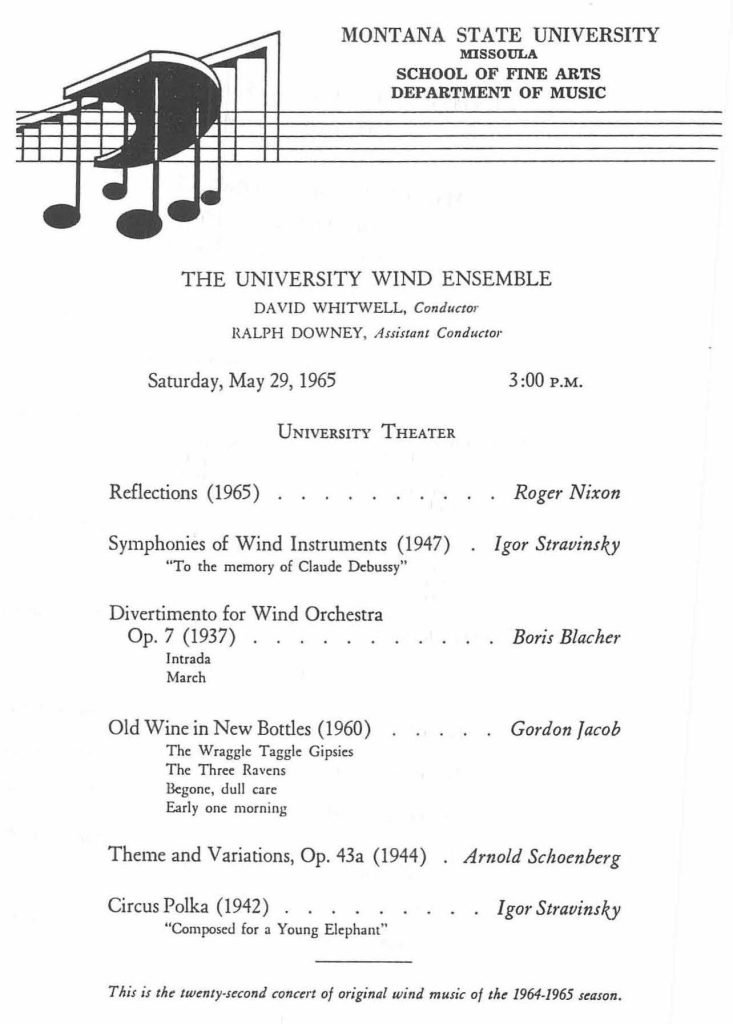

To help call the attention of the profession to the fact that one could actually do this, and still have interesting programs, I began to carry a phrase on the bottom of my programs which read, “This is the tenth concert of original wind music of the 1964–1965 season,” etc. (I counted repeat concerts, of course). I then mailed these programs to other college band directors and it became a much remarked upon tradition and drew considerable attention to the Montana band program.

Toward the same end, I began writing more articles for journals on the subject of the band’s repertoire. These articles also were much discussed. In an article in the Montana state education journal, “Band Conductors Born in 1965: What will be their Heritage?,”1 I tried to get the high school conductors to think about their cultural impact on their community. Speaking of these band directors to be, I wrote,

Will the band literature they perform reflect the best efforts of their contemporary composers? Will it include at last the many fine compositions, yet unpublished, by serious composers of the 18th and 19th centuries? Surely we will not wish to pass on to them, as reflective of our society, the endless stream of commercial trash which floods our market.

…..

I wish the individual conductor had more real understanding of the tremendous impact which he has on the musical life of his community. His program, performances and pay all bear direct influence on the future. It is not easy to look ahead two decades, but it seems unfair to our successors to look ahead only as far as the next concert or the next season. Surely we bear a larger debt to the future than a successful present.

In an article for the MENC Journal, “The College Band: Can it Escape its Heritage?,”2 I wrote again of my hope for the future.

The real concern among the younger conductors is whether we can continue to justify any musical medium which does not perform its own art. The many young conductors I have talked with lead me to believe that the years ahead will see a radical change in the nature of the band. There is even talk in many circles of avoiding the word “band” because of the connotations it carries.

The conductors of any generation have a tremendous responsibility to the future. The performances of today will form the heritage of tomorrow.

I also published this year three extensive monographs, listing music for winds and voices, which were commissioned by the American Choral Foundation.3 4 5

The article which had the greatest impact was one called, “Three Crises in Band Repertoire,” published in the March 1965 issue of The Instrumentalist.6 This article dealt with three periods during the twentieth century when important composers were writing wind music out of their own interest, while band directors ignored this activity and continued to perform mostly transcriptions. I received many letters from other college band directors commenting on this article. The great majority were letters of praise and many indicated that the writers had begun to give serious thought to the question of the band repertoire. One such letter came from one of the most respected conductors in the profession, Walter Beeler, of Ithaca College in New York. He wrote,

It is my feeling that your article describes the state of affairs about as well as I have ever seen it done. It is also my feeling that this is a much needed type of article for our profession. I am in full accord with your suggestion that most of our bandsmen incline to follow tradition blindly, merely because it preceded them. Unfortunately, this has resulted in our maintaining and perpetuating most of the dreadful literature that early bands were obligated to use.

Another encouraging letter came from Allen P. Britton, then As- sociate Dean of the School of Music at the University of Michigan.

The ideas you express are excellent and I wish you every success in bringing them to the attention of band directors everywhere and also in seeing that band directors begin to perform some of the very wonderful music written for wind instruments. It has always seemed strange to me that most of the good wind instrument literature available remained comparatively in neglect.

I received one extraordinary letter from a former band director, Martin Sherman, of Rutgers University, who had become bitter and left the profession due to the poor literature played by the profession. He wrote, “I am now out of the band movement and a great deal happier about my life in music because I am no longer part of an activity dedicated to fourth-rate music and commercial values.”

I also received a long letter, with extensive points of agreement, disagreement, and suggestions for rewriting, from Frederick Fennell, of the Eastman School of Music. While he found the article in general, “interesting and historically vivid,” he expressed several times his dismay that I did not mention his work with the Eastman Wind Ensemble.

Perhaps you also know that I am convinced from that history that the name of the group has been a major deterrent to the “acceptance” of the wind medium by composers of the first rank, and although you elect to ignore both the existence of the Eastman Wind Ensemble and its recordings as musical and educational factors which, “… would enable those of us active today to take advantage of our present opportunity.” I wonder if you really mean to cut us out of your view of history?

In so doing, you have denied yourself a valid point and ignored the only guide to playing—as well as to what to play—that the wind band movement has really ever had in this country. It has been, and remains, a consistent commitment; in the discs is an undeniable commitment and I am amazed that it escapes you. Perhaps you’d like to tell me why—at least I should like to know.

Fennell also commented on some of the famous men of our profession and their role with respect to the band’s repertoire.

I wish Dick Goldman really liked the band, but he does not—and it shows.

…..

You must include a repertory blast at [A. A.] Harding, for it was his kind of concerts that set the whole pattern for A. R. McAllister & Company and thus for the school band movement in America. While you are calling spades, you may as well make them jet-black.

It was obvious from this letter that I had hurt Fennell’s feelings and I felt badly about that as I read the letter. Furthermore he was absolutely correct, I should have mentioned his contribution. Improbable as it may seem, the justification I have to offer is that in 1965 I had not yet heard any of his recordings and did not understand the impact he had already made on the profession. The first time I ever heard of this ensemble, or even its host school, was during a visit to a girlfriend in Minneapolis during the Christmas of 1955, when she showed me pictures of her high school wind ensemble, conducted by Butler Eitel, which was modeled after Eastman. I had, in other words, been at Michigan for a full semester and had never heard mention of this ensemble. The only other time I remember ever having heard the name mentioned was at a party attended by my horn teacher, who had been a member of the first Eastman Wind Ensemble. I don’t recall now how it was expressed, but the message I got was that this was not a topic for discussion in Ann Arbor—due, I supposed, to being a rival philosophy. In retrospect I am sure the “Wind Ensemble” topic must have been much discussed among college band directors themselves, during the period I was an undergraduate student at Michigan, from 1955 to 1959, but I don’t believe my fellow students and I ever heard much about Eastman. During the following four years I was in the military and consequently completely out of touch with the civilian academic world, something which can probably be understood only by one who has been in the military (there was a large sign for drivers leaving Bolling Air Force Base in Washington which read, “Beware, you are entering the civilian sector!”). And so, I was simply late in coming to know this man and his work. Needless to say, after receiving his letter I bought all the recordings I could get and through them immediately came to understand what he had done for the profession.

I felt so badly about this oversight that I don’t think I corresponded with him until after we met at Eastman in 1972 when we were both guest conductors on a concert there. In fact I recall that I was somewhat hesitant about the prospect of encountering him on this occasion, but he was at once friendly and complimentary of my conducting and made it evident there were no hard feelings. Thereafter we remained very close friends and there have been numerous times when I turned to him for advice. And I should add, whenever I had the opportunity to hear him conduct it was always a master lesson for me.

Finally, regarding publications, I began in this year a long series of some seventy-five articles in The Instrumentalist magazine, which ran until September 1977, on the general topic of the association of famous composers and bands. This series found many readers since before this time none of us had ever had any discussion of bands in our university music history classes.

With regard to my work at the university this was an extremely successful and satisfying year. During this year I became fully confident of my ability as a conductor and was looking forward with confidence to this being the profession for me. Ironically, I was presented, during this year, with two opportunities to leave the field of education. The first came from Ted Jacobs, President of the First National Bank of Missoula (which he owned). He invited my wife and me to his home and pleaded with me to let him train me and place me in the banking profession. I was honored by his attention, but could not tell him that to me it seemed a rather boring way to spend one’s life.

The second offer came in the form of a phone call, and subsequent letter, from Traugott Rohner, the publisher of The Instrumentalist magazine. He offered me a salary nearly double my university salary to become the Editor of this influential journal. This offer had some appeal for me, not the least of which was the prospect of living in Chicago, a city I loved. He suggested that in this position I would have “a tremendous influence throughout the country.” He also suggested it would not be so difficult to give up conducting as I might think. “The applause of the audience is very transitory while the satisfactions of the printed page are much more lasting.” However, a large part of the job was selling advertisements, which included visiting members of the music industry and, in effect, begging for money—something which I did not believe I would enjoy doing.

This was my first year of marriage, which has to be a most memorable part of anyone’s life. Since Giselle and I had argued over religion extensively during our courtship, it was our plan to attend a “compromise” church in Missoula. Indeed, during my first year in Missoula I found and attended a wonderful, small Episcopalian church which had a minister who was an excellent speaker. I had written to Giselle, before we were married, assuring her how happy we would be attending there together.

However, the week before I left Missoula to return to Washington to be married, this minister announced to the congregation that he was leaving the ministry to become a lawyer! When we returned from our honeymoon, the new minister was in place and we attended church the first Sunday after our arrival. This new minister turned out to be from California and was a rotund man whose style was telling jokes throughout the sermon. The very next Sunday we accepted an invitation from a new choral conductor on the faculty, Donald Carey, to teach us how to ski. We not only fell in love with skiing, but found that being in nature on Sunday morning was also a form of spiritual revival. While we lived in Missoula this became our custom.

The ski area near Missoula, by the way, had a very rugged alpine atmosphere and to learn to ski there as beginners, with those old wooden skis and string laced boots, was not easy—especially as Don’s form of instruction was to take us to the very top and teach us on the way down. However, by learning to ski there we found we could ski anywhere else in the world with ease.

Just before Christmas vacation Giselle and I drove to Tempe, Arizona, for the National Convention of the CBDNA. It was the policy at that time to elect divisional officers at the national conventions so I decided to run for President of the Northwest Division. In the subsequent election I came in second and was therefore elected Vice-President. I was disappointed in the election, which was no doubt unreasonable considering I had nevertheless attained national office in my profession while in only my second year of teaching. While there, Jack Lee, the Grand President of Kappa Kappa Psi awarded me an honorary life membership in this fraternity “for my record of outstanding contributions to the band field.”

After the convention we drove down into Mexico, to a beach town for a vacation. On the long return drive home we entered Montana on Christmas day. Towns in western Montana are few and far between and at the point we were nearly out of gas we arrived at a town so small that it occupied only one side of a street of about three blocks. The only sign of life seemed to be the local bar and as it had a gas pump we stopped. There we found everyone in town who had no place to go on Christmas and they were all drunk. I had to wake the owner in order to get enough gas to continue our trip. We were very tired, but we decided that we would push on to Butte for a nice Christmas dinner before continuing to Missoula. Butte also seemed closed for the day and the only place open to eat was a small, unimpressive Chinese cafe. We were rather despondent on this, the first Christmas of our married life together!

Notes

- David Whitwell, “Band Conductors Born in 1965: What Will be Their Heritage?,” Cadenza, January 1965. ↩︎

- David Whitwell, “The College Band: Can It Escape Its Heritage?,” Music Educators Journal 51, no. 6 (July 1965): 57, https://doi.org/10.2307/3390457 ↩︎

- David Whitwell, “Music for Voices and Brass Ensemble,” The American Choral Foundation Research Memorandum Nr. 53, December 1964. ↩︎

- David Whitwell, “Music for Voices and Trumpets, Horns, or Trombones,” The American Choral Foundation Research Memorandum Nr. 56, April 1965. ↩︎

- David Whitwell, “Music for Voices and Mixed Wind Ensembles,” The American Choral Foundation Research Memorandum Nr. 61, December 1965. ↩︎

- David Whitwell, “Three Crises in Band Repertoire,” The Instrumentalist, March 1965. ↩︎