Articles and Monographs

- David Whitwell, “The Future Role of the Marching Band,” Cadenza, January 1964.

- David Whitwell, “Let’s Throw Away the Score,” The Instrumentalist, April 1964.

- David Whitwell, “Would You Like to be a Band Conductor?,” The School Musician, May 1964.

- David Whitwell, “The State of Bands in Montana,” Cadenza, May 1964.

In February 1963, I received one of the numerous job notice cards sent to me by the Lutton Personnel Service in Chicago, which at the time was the only way to really hear about jobs all over the country. The position, at the University of Montana (then called Montana State University (MSU)), seemed ideal for a first job, as it was advertised as mainly teaching horn and playing in the faculty woodwind quintet. Even though it was advertised as a one-year vacancy for someone on leave, I accepted the appointment when it was offered over the phone in early April because it had become apparent that it was going to be difficult to obtain any college job without experience. The contract was for $6,000 per year with the understanding I would finish the doctorate by the time school began.

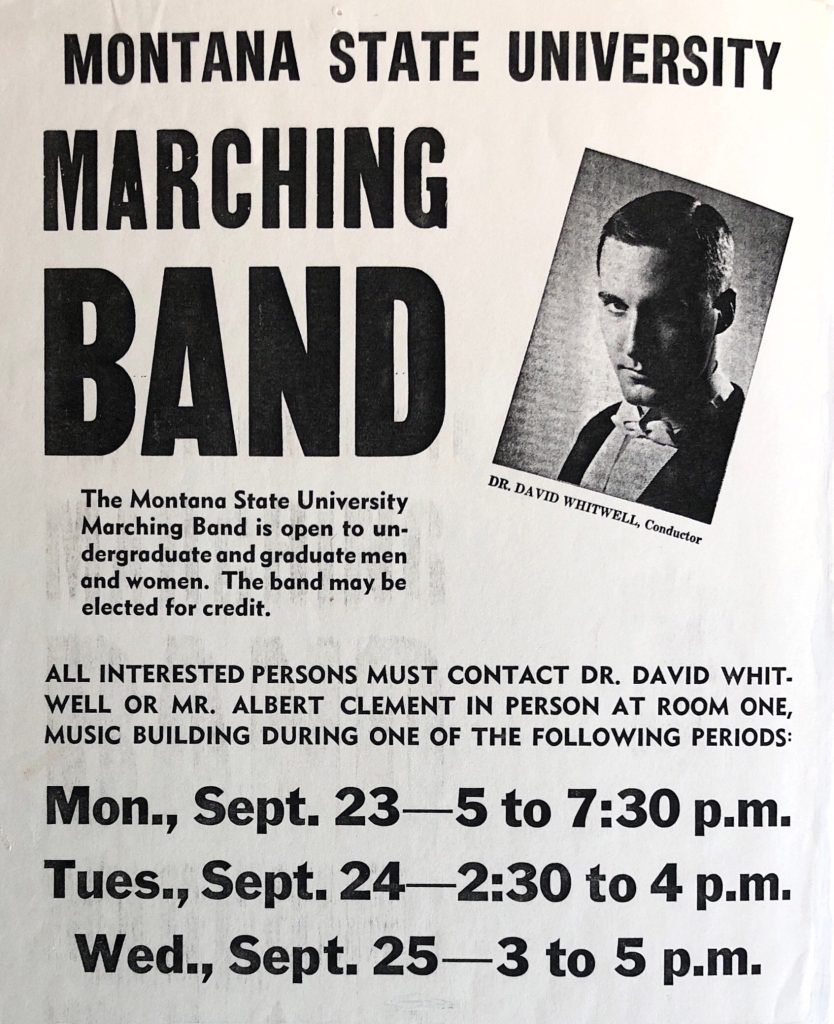

The rest of the Spring and early Summer, still back in Washington, DC, I was absorbed with finishing my dissertation in order to complete the PH.D. As I had heard nothing further from Montana during this period, in late June I wrote the chairman of the music department to inquire about my precise teaching schedule in order to begin any preparation which might be necessary. His answer, on 1 July 1963, contained a bombshell! He informed me that among other teaching responsibilities, which included being the private teacher for all horn, trombone, tuba and percussion students, teaching a music education class and a theory class, I would be in charge of the marching band! This had never been mentioned by anyone previously and if it had I would never have applied, for at the time I was not even applying for band jobs, much less marching band jobs.

I was immediately thrown into a state of panic and at first saw no possibility that I could accept such a position. While I had had four years experience in the Michigan Marching Band, I had never had a course in marching band techniques. Even if I were experienced in running a marching band, the fact that I would only be arriving in Missoula the week before classes began would obviously leave no time for preparing a marching season. I was about to call and withdraw from the position when someone mentioned that there was an oboist, Jerry Domer, in the Army band who was a graduate of Montana whom I might contact. I called Jerry and explained my situation. He urged me to go ahead and take the position, saying that the marching band was so bad that no matter what I did it would be taken as a great improvement. Since it was clearly too late to find another position, I decided to take his advice and gamble. As it turned out, Jerry was correct. Upon arrival I viewed some films of the previous marching season and it was immediately apparent that the previous conductor simply did not take the marching band seriously.

The town of Missoula, as I first found it, seemed in some ways like a western outpost of the nineteenth century. The only department store was still called a “mercantile” store and the medium of exchange was the silver dollar—there were no paper dollars at all. This reminds me of a day soon after I arrived when I was visited by a young Army officer who informed me that he was there to take the annual survey of government instruments. It seems that during the Civil War there had been a Fort Missoula, with a band, and when the war ended, and the post was closed, the government gave the band instruments to the university. The university’s only responsibility was to maintain them, but when the officer showed me a list of nineteenth-century instruments like helicons and cymbals “with pouch” to be installed on a horse, I had to inform him that I was quite sure no such instruments existed. He produced a document which all of my predecessors had signed for nearly a century, but apparently he was the first officer who actually wanted to see the instruments. This was followed by about two years of paper work necessary to have the instruments removed from the inventory of the United States!

The faculty was generally capable but, like the area, they were very conservative and not eager for change. I soon discovered that the wiser course for me was just to forge ahead and develop my own program without consultation, and I was happy to discover they allowed me to do this without restrictions or objection.

Since I arrived just before classes started, I had no time to prepare the marching season, so I just wrote the shows, and music, one show at a time and somehow got through the season. The only marching show style I knew, from Michigan, at that time, was the old “picture show” format: picking a story, finding music which had some remote topical relationship, and then designing stick-figure formations and script to carry out the story. While such “pictures” could be seen from the high Michigan stadium, it was soon obvious that the concept had little effectiveness in a small stadium such as the one in Missoula. I was therefore very pleased when another college band director, Otto Werner, who traveled to Missoula with his school’s team, sent me his “personal compliments for a very fine performance in extremely cold weather,” and asked if he could borrow some of my ideas for use the following year.

I had approached both the music rehearsals and the field rehearsals with a very serious manner and demanded an unknown, for Montana, level of discipline and precision. As a result, this first marching season generated considerable enthusiasm among the faculty and the student body. The Dean of the School of Fine Arts, Charles Bolen, sent me a nice letter of congratulations.

The degree of success which you have achieved with the marching band this fall has been most unusual. I certainly want to congratulate you on the fine performances which the band has achieved this year.

From many people I have heard nothing but compliments about the band this year. I am sure you have the satisfaction of having done a job remarkably well.

I established the tradition of a Marching Band Banquet after the last game which gave me an opportunity to thank the students and to talk with them about my philosophy of the university marching band. I also talked about the state of the concert band literature and this was the first of many speeches and articles during the following years in which I made an effort to move the profession toward a repertoire of original wind music. On this occasion, I told the students,

I believe the future of band music is contingent upon a revolution in the standards of wind literature. I believe that the next two decades will see this revolution and that those of you here will enjoy an aesthetic delight far greater than you may have thought possible through this medium.

I sent a copy of this speech to a number of college band directors around the country and was surprised when two separate editors of The Instrumentalist magazine, Al G. Wright and Richard W. Bowles, immediately offered to publish it. However, I had already sent it to the state music education journal where, in January 1964, it became my first publication.1

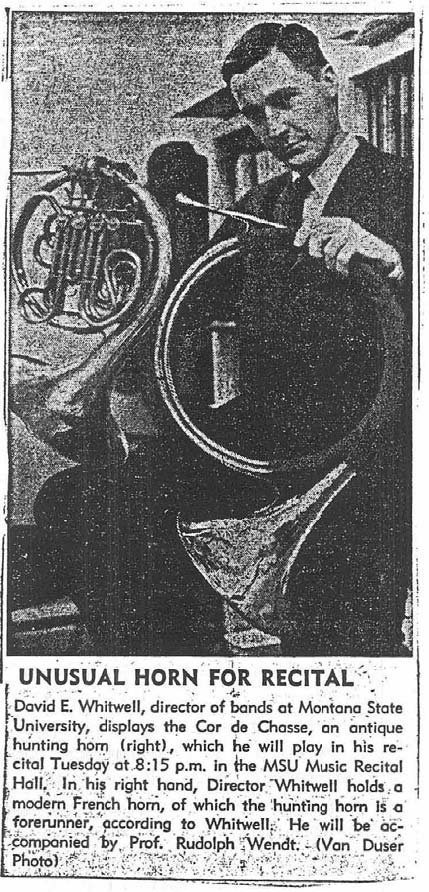

At the end of the marching season, I used the few remaining weeks of the Fall Quarter to prepare an indoor concert with the band, performing the Holst E-flat Suite,2 some Leroy Anderson pieces, marches, and school songs. I treated this as a formal concert and when I appeared on the stage in white tie and tails it was the first time anyone on the faculty had worn tails. Thereafter, everyone did. My first set of tails, by the way, I had purchased in Washington, DC, as did my friend, Erik Shaar, for the purpose of having formal pictures made for job applications. Since we were quite broke, after paying for our graduate work on an enlisted man’s pay, we bought our tails from a store in one of the less advantaged parts of Washington which specialized in renting tails for funerals. They would take them off the bodies after the funeral and then rent them again or sell them! I wore this set of tails for twenty years!

All of this, together with the fact that I had conducted the marching band and a brass ensemble all Fall without scores, created a tremendous impression on the administration and when, in the Spring, the person I was replacing elected not to return I was given

a regular contract for the following year as Director of Bands. It was clear from discussions with my predecessor’s friends that a primary reason he felt he could not return was due to the tremendous enthusiasm on the part of students, public, and administration which I had generated for the marching band.

One of the pleasures I had at Montana was in working for their new President, Robert Johns. He, in addition to being a very vocal supporter of mine, was that very rare administrator who immediately solved any problem I presented to him, never sending anything to a committee or seeking other consultation. For example, the marching band rehearsal field was smaller than the size of a football field, due to a large tree on one end of the lot. I explained to him the necessity of having a full-size field to rehearse on, expecting that he would assign me any of several other open spaces. Instead, the next day a crane appeared and removed the tree! In other words, for him the problem was not one of space but the tree!

On another occasion I was able to help him solve one of his prob- lems. A very wealthy rancher in Dillon, Montana, on a trip to New York City had fallen in love upon hearing one of those massive Wurlitzer theater organs and became determined to own one. Eventually he was able to buy one and had it installed in the huge living room of his ranch house in Dillon. His wife immediately gave him the choice of no organ or no wife, so he called up our president to see if he could donate the organ to the university. The president, not wanting to say no to a man who was frequently making gifts to the university, said he would look into the possibility. The president then looked at his faculty phone directory to see who was the organ professor. This faculty member, a PH.D. in musicology from Indiana University, said “No.” He explained that having a Wurlitzer would make him an outcast among university organists, etc., none of which was understandable to the president. It was at this point that I first heard about this problem and I immediately called up the president to recommend we install the Wurlitzer in our massive basketball field house. The president was delighted and thankful, and then called back the organ professor and told him that part of his load henceforth was to play this organ at every basketball game! I can assure the reader that none of this reflected the fact that I never enjoyed watching basketball and was thus now relieved from the responsibility of organizing and rehearsing a basketball band!

In another year, I found I did not have the funds to take the marching band to the big rival game in Bozeman. I presented this problem to the president and he immediately gave us a plane which belonged to the university for the trip. If ever I should have a footnote in the history of the American marching band, it must be for this occasion when the band flew, while the football team bounced along for six hours in school buses to the game! Who will not agree that this put things in their proper perspective!

Montana had the only all-wood stadium in the country, donated by the basic forest industry of that state, and like anything else made of wood was in poor shape due to being exposed to the elements for many years. Whenever the president brought up the subject of the need of a new stadium, he encountered the inevitable response, “But, we already have a stadium!” One day the stadium burned to the ground, which effectively answered that objection, and the rumor was that he and a vice-president had burned it. Montana was a very conservative area (Missoula was the home of the John Birch Society), and so one can understand that anyone with this kind of direct problem solver would soon be sent packing. He left the same year I did, but I thanked my lucky stars for his support while I was there.

Speaking of this suspected arson, I am reminded of an occasion when I also considered such a solution for one of my problems. Montana, when I arrived, had perhaps the most unattractive band uniforms in the nation—they were gray and old. There was a student on campus who was the son of an important diplomat in Washington, DC, representing a Near-East country. One day a faculty member’s car was burned and while it was common knowledge that the student had done it, the university decided to do nothing due to possible international repercussions. Then a month later the student burned down the Art Department and again nothing was done! It passed through my mind that I might approach him to burn my uniforms; he could have the fun of setting another fire and I would have the perfect excuse to get new uniforms! But, since the uniforms were housed in the basement of the music building, I decided perhaps this was not the best solution.

The primary assignment in my job, as advertised, was playing in the faculty woodwind quintet. I will never forget those first rehearsals. The Dean of the School played flute and, as Dean, did not want to appear to dominate the rehearsal, so he would say nothing. The clarinetist was a very shy man who would never say a word and the oboist was only part-time and felt that as such it was not appropriate to offer suggestions. The bassoonist was a graduate student, so he felt it was not his place to offer suggestions and since I was new I hesitated to take over the rehearsals. Consequently, we would play through some movement of a work and, at the end, would put our instruments down and sit in silence. Finally, someone would say, “Well, maybe we should play it again.” I, of course, coming from four years in Washington where I performed 1,100 concerts and rehearsals were almost non-existent, was silently going crazy with these ineffective rehearsals and the wasted time.

Early in the Fall we performed on a joint concert with the faculty string quartet and the local paper reported,

The Woodwind Quintet seemed to have some trouble with pitch in its presentation of Beethoven. This composition is indeed trying for the French horn; however, this part was handled very admirably by an addition to the music department faculty. Mr Whitwell is indeed an addition to the quintet and I wish to welcome him to the campus.

Soon after this concert, the bassoonist actually blew a hole in his esophagus causing the quintet to disband. Since it was a considerable proportion of my faculty load, this gave me much needed time for the marching band planning.

Another part of my load was teaching trombone, an instrument I knew very little about. I announced to the students that since this was the university level I would not deal with matters of simple technique, but rather only with musical problems. Of course, that didn’t fool anyone, but I perhaps gave them some help until we hired a graduate student the next year who was a specialist in low brass. I was also the percussion teacher, but this was an area in which I had actually done some teaching and at least knew the basic rudiments. By organizing the first percussion ensemble concert I was able to keep these students happy and the following year I worked out a plan where a specialist flew in from Spokane to teach regular lessons.

It was also required that the faculty play in the Missoula Civic Symphony, conducted by the faculty violinist, and the Chamber Band. The orchestra played good music but the quality of performance was poor and the rehearsals were long and tedious. I continued to play in the orchestra for four years, but when I became Director of Bands the first thing I did was remove all the faculty from being required to play in the bands—much to their delight.

The most difficult adjustment for me in Missoula was the isolation, something I never did adjust to. The small town newspaper carried almost no national or international news, and I had been used to the great Washington Post. Television was all local production, with the exception of one cable channel. This one outlet to the outside world, however, was controlled by its very conservative owner and Missoula only saw what he thought it was appropriate for us to see. I remember, for example, one night when one of the Mohammed Ali fights was to occur there suddenly appeared an American flag on the screen and a voice-over said that, due to some anti-war comments by the fighter, Mohammed Ali was un-American and thus the fight would not be shown! Another example of this conservative atmosphere came at commencement when I played a short Nelhybel composition and I was attacked by a faculty member for playing an un-American work. My answer was that Nelhybel was an American!

One of the delights of this first year of teaching was due to the fact that I was a young eligible bachelor. Consequently I enjoyed a level of popularity with the students only possible in such a circumstance.

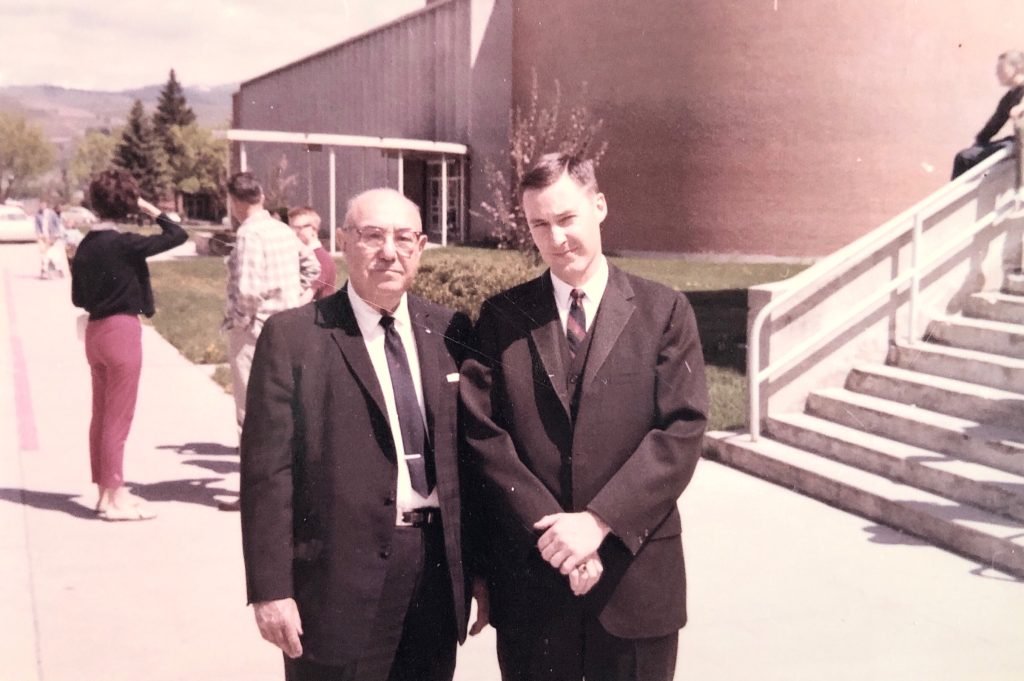

Another pleasure of working in Montana came from my association with the grade school band director, Roy Lyman. He was very enthusiastic, a super teacher, and had developed one of the finest programs in the nation. Each year he made possible the funds for a festival with the grade school band, the high school band, and the university band playing with some important guest. This first year the guest was Frank Simon, who gave a great presentation using the music of Sousa.

During the Air Force I had played a lot of golf and although the local civic course was not a good one this continued to be my primary form of release. The first week I arrived in Missoula I was invited by a distinguished older faculty member to play at the Missoula Country Club, a really fine course which my salary did not permit me to take advantage of. This distinguished gentleman had been the state secretary of music in Virginia and later had been a national president of the Music Educators National Conference (MENC). Upon retirement he was hired for ten years as Dean at the Cincinnati Conservatory in the East, retired again, and was hired by Montana. Consequently, when I knew him, he was a bit senile. On the first green we hit our balls and walked off in our separate directions, coming together again only on the green. When we arrived on the green, he said to me, “… and what would you have done in that circumstance?” He had had an imaginary conversation with me while walking toward the green and I had to answer without having any idea what the conversation was about! This continued on each of the remaining seventeen holes and one can imagine my dilemma, being a brand new young faculty member in his first job not wanting to offend, in having to think of seventeen answers appropriate to conversations I was never party to.

In the Spring, after it was announced that in the following year I would be the next Director of Bands, I drove across the state to meet as many of the high school band directors as I could. Since Montana is more than six hundred miles across, this turned out to be a trip of nearly two thousand miles. As there were great distances between towns, and no speed limits at that time, I was blazing through Eastern Montana at the highest speed my VW would produce when it actually blew up seventy miles from the town of Glasgow. There I found myself on the Saturday before Easter, with no money and, just being out of the military, no credit. Fortunately for me, and another example of a bygone era, I called up the President of the First National Bank of Missoula at home and he told the car dealer to just give me a car and he would cover everything!

In visiting the schools, much of the teaching I found to be hindered by the fact that there were just no good models—how can one develop fine clarinet sounds, if the students had never heard a fine clarinetist? In some schools I found band directors with no formal music education at all and nearly everywhere I found a very poor standard of band literature. In another article, “The State of Bands in Montana,” in the state music education journal,3 I was very forthright about these issues. I knew there would be some angry band directors, but I felt a strong desire to put the cards on the table and make it very clear that there was going to be an entirely new standard in the state as far as the university and I were concerned.

Some of these issues returned when I adjudicated a district band festival and gave ratings which were a bit lower than some ensembles had experienced in the past. I remember I gave a “II” to an orchestra from Spokane which had never received less than a “I” before and I received a letter filled with personal threats and profanity from the conductor. This was the first occasion I experienced the “festival” system which in our country is so corrupt and dishonest. I have never met an adjudicator, myself included, who gave the ratings he felt the groups really deserved. The foundation of festival adjudication is especially flawed by the fact that the adjudication form demands that we judge the band, whereas everyone knows what we are really hearing is the conductor and the effectiveness of his teaching—which is never judged. Years later I submitted to Southern California band directors a new format to correct this,4 but it found no enthusiasm—after all, the high school conductors are protected by a system that removes them from guilt by association. It is no wonder that many of my colleagues throughout the nation and I no longer participate in adjudicating in these events.

During the Winter and Spring Quarters the direction of the band program was given over to the clarinet teacher, by prior arrangement, and I had to sit back and watch all the discipline and musical standards I had set during the Fall disappear. Finally, I was allowed to conduct the greater part of a concert during the Spring and I was able to again begin to raise the musical demands. This was my first public appearance with a concert band and my portion of the concert included the Strauss Serenade, op. 7, the Gounod Petite Symphonie, the Barber Commando March, the Rossini Italian in Algiers, and Schuman’s Chester. I have a tape of this concert and while it certainly does not sound impressive to me today, at the time it was said to be the best performance in the history of the school. I was very pleased that Wayman Walker, Director of Bands at Colorado State College in Greeley, who happened to be present, wrote,

I certainly enjoyed your band concert and especially meeting you. I’m sure we will be hearing great things about the Montana University band from now on.

Late in the Spring I had my first articles published in national journals. The first, “Let’s Throw Away the Score!”,5 in The Instrumentalist, spoke of score study and memorization. The second, “Would You Like to be a Band Conductor?”,6 in The School Musician, drew on my own education and experience as a beginning conductor.

When you begin your college career you will find a curriculum containing many education courses. These will adequately prepare you for teaching, but not for understanding the music you will be conducting. You will have to take it upon yourself to insure that you receive a solid background in theory. The principles of 18th century theory, which you will automatically receive, will not be sufficient.

……

For those of you who adequately prepare yourselves, an exciting career awaits you. Your place in music will be far more respected, far more demanding, and far more satisfying than you can possibly anticipate now. The field of music eagerly awaits the entrance of serious youth.

At the conclusion of the school year, after arranging to rent my house to the distinguished visiting scholar, Karl Geiringer, I drove to Washington, DC, to be married to Giselle Eckhardt. We had elected to be married in the backyard of the family she had lived with, never having been able to agree on a Protestant church, for me, or a Catholic church, for her. For our honeymoon, we spent some time on the beach in New Jersey and then visited the World’s Fair in New York, before making our way back to Missoula.

Notes

- David Whitwell, “The Future Role of the Marching Band,” Cadenza, January 1964. ↩︎

- Gustav Holst, Suite in E-flat, op. 28, no. 1 (1909) ↩︎

- David Whitwell, “The State of Bands in Montana,” Cadenza, May 1964. ↩︎

- See the chapter, “A Proposal for a New Festival Format” in David Whitwell, Essays on the Modern Wind Band, ed. Craig Dabelstein (Whitwell Books, July 14, 2013) ↩︎

- David Whitwell, “Let’s Throw Away the Score,” The Instrumentalist, April 1964. ↩︎

- David Whitwell, “Would You Like to be a Band Conductor?,” The School Musician, May 1964. ↩︎