Public Appearances

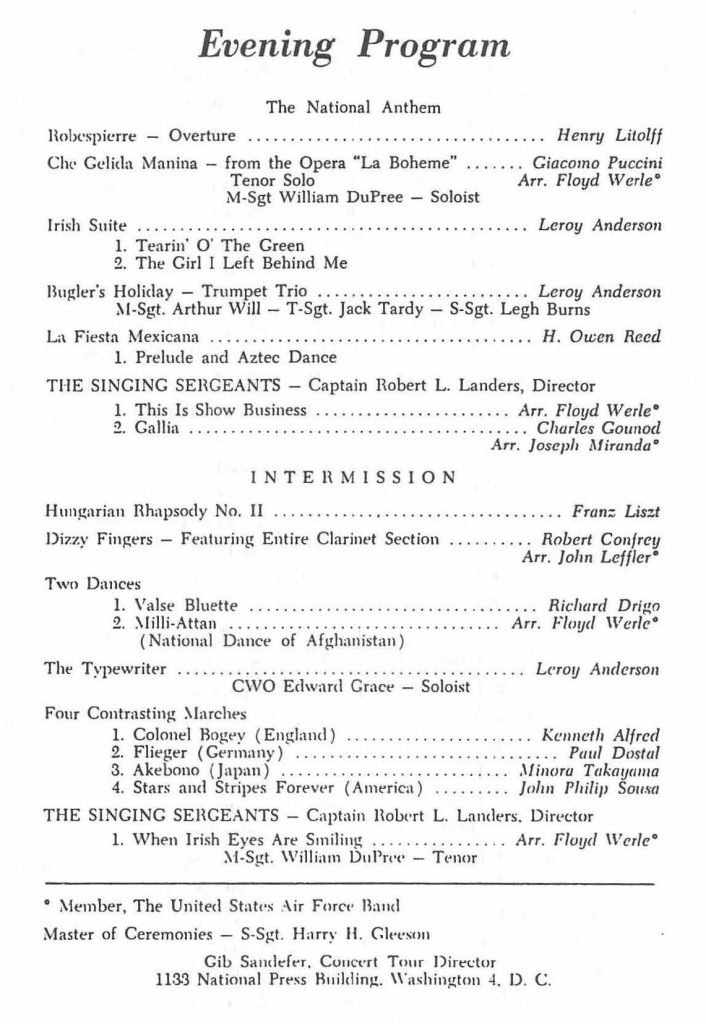

Performed more than 1,100 concerts throughout the Far East, Canada, Mexico, and the United States as Associate First Horn, United States Air Force Band and Orchestra, Washington, dc.

Two weeks after my graduation ceremony at the University of Michigan, on 1 July 1959, I joined the United States Air Force in Oklahoma City and within a few hours found myself in that curious environment known as, “Boot Camp,” which in my case was Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas. Boot Camp, as I knew it, was a twelve-week course which had very little to do with skills or job training needed by the Air Force. All that would come later when one was assigned to a specific career slot in the Air Force. There was also very little in the way of military orientation other than a few courses in things like the history of saluting and a few hours of weapon instruction.

The real purpose of basic training was psychological. In a few short weeks the military must attempt to remove all traces of individuality (which begins with shaving off everyone’s hair, of course) in order to produce a being who will think of the Air Force and not of self. Only by doing this can the military produce a person who will follow, without thinking of self, an order to march forward and die in battle. If one thinks of self, of course, no rational person would do this. Aided by having the recruit in an environment completely closed off from the rest of the world and by constantly telling you that they can shoot you for disobeying the most minor command, they are extremely effective in this psychological rebuilding of the mind. I was not aware myself how effective this all was until I drove to Ann Arbor, where I had left some personal belongings, on the way to Washington, DC, after my basic training was completed. As I arrived on campus I became aware that nearly all memories of the four years I had just spent there had disappeared from my conscious memory. I spent several days there just walking around the campus looking at buildings, etc., and as I did memories would return and I was gradually able to reconstruct my real personality. In retrospect, I found this quite amazing and frightening.

Teaching discipline was another goal of basic training, of course, and a necessary one as the cross section of the population one finds in a group of recruits includes many who have never experienced anything remotely characteristic of “discipline.” Practice in marching, I think, had something to do with this. In any case enormous blocks of time were spent marching back and forth in the near unbearable Texas sun. One of the most difficult aspects of this endless and aimless marching for me was the fact that for hours on end there was absolutely nothing for the mind to do. This, together with the sun, made it very difficult to stay awake, even though one’s body was marching down the street. I had one strange experience in this regard, when I suddenly had the experience of waking up and finding myself several blocks down the street from where I was in my last mental awareness. I think my body was so conditioned at that point as to continue marching while sound asleep.

One of the most difficult things in the beginning was in making the effort to be as anonymous as possible. Here I must explain that at this time every male who was unmarried and not in college had to either join the military or be drafted. Being drafted meant being the lowest foot soldier, whereas by joining one had the opportunity to at least serve in a field of interest. In my case this meant a guarantee of being in the band and orchestra in Washington plus a promotion every month after basic until I reached the rank of Staff Sergeant. It was obviously necessary to keep all this secret from the drill sergeant who had taken perhaps twenty years to reach this rank. Therefore I would be called in from time to time and be berated by the drill sergeant as being a person without ambition—“You have a college degree. Why don’t you want to be an officer? You must be stupid!”

On one occasion I made the mistake of dropping my anonymity; I offer the story as an example of military thinking. One hot afternoon we were in the barracks sitting on our footlockers, something we frequently did when they had nothing for us to do, when a sergeant entered and asked who among us could type. Being aware that the clerical building next door was the only air conditioned building, I and one other person raised our hands. We were taken out and as soon as we were out the door we were each handed a shovel and given the task of digging up and re-cementing about thirty clothes line poles.

Since the first few weeks consisted of such total boredom, I accepted a transfer to the camp drum and bugle corps even though this meant an additional week in basic training. Again I was punished by volunteering, for this primitive ensemble played only one simple march over and over each day while troops learned to march to music. It was, of course, much more boring.

The whole experience must be similar to being in prison. At first one counted the days, but this seemed to only make the time go slower. On the day of our release we were all gripped with fear that in the next moment someone would tap us on the shoulder and say, “You have to stay another week.” Only when the wheels of the airplane left the runway did one begin to believe that one was actually free.

When I arrived in Washington the band was on tour and therefore my only duty was playing with the orchestra. This was wonderful for about a week until a curious thing happened. The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, the highest ranking military person, had a son who had been a rather untalented piano major in college (no university would turn down the son of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs!). After graduation this young man, again because of his father, had been given the opportunity to make his first appearance as a professional pianist in the Beethoven Third Concerto1 with a regional orchestra. His father ordered the Air Force Orchestra, the only military orchestra in Washington at that time, to serve as a rehearsal vehicle for his civilian son. Therefore for an entire month, day after day, we did nothing but play through the concerto, from beginning to end and then once again back to the beginning, while the young man struggled to learn his part!

This reminds me of another occasion when some South American composer came to Washington with a new orchestral composition and for diplomatic reasons we were ordered to play and record his work. I recall on this occasion the poor quality of the work itself resulted in our rather inattentive performance. At one point the composer, who was conducting and who spoke no English, stopped us and, in a rage, screamed at us in what was obviously Spanish profanity. When he stopped, his wife, who was translating during rehearsal, very sweetly said, “Gentlemen, the maestro asks if it could be a little softer!”

The Air Force Band at this time consisted mostly of older men who had been trapped by World War II and were serving out their twenty years before retirement. Many of them had been members of great orchestras before the war and were outstanding players and musicians. I learned a great deal from them about music, performance, and the professionalism of the art. I recall, for example, an interesting psychological lesson I learned during the very first rehearsal I played when the full band returned from tour. I was assistant first horn and as I was playing I missed an attack or two—something which had always been rather overlooked in my experience as a horn player (“The horn is such a difficult instrument!”). The first horn player, a man who had been a member of the Boston Symphony, leaned over to me and said, simply, “We don’t miss notes.” And from that day on I played with a level of accuracy which earlier I would have never believed I could have achieved!

It had been predetermined that the five or six young men coming into the band would also be members of the Singing Sergeants. None of us wanted to do this because it not only conflicted with the orchestra but meant a great deal of extra duty, as the choral group was constantly performing around Washington. Therefore when we “auditioned,” which consisted of singing together, “Oh Come All Ye Faithful,” we made every effort to sing out-of-tune, with wrong pitches, and horrible intonation. No sooner had we struggled our way through than the Captain leaped up and cried, “You’ve made it!” Fortunately for my plans to attend a university while I was in the Air Force, the first horn player went to the Commander and had me removed from the Singing Sergeants and returned to the orchestra.

The most interesting experience with the band was the touring. This included not only the priceless experience of a tour of the Far East, but performing in countless towns in virtually every state except for the South. The South was off-limits as we had a brilliant black tenor soloist who, at that time, could not be assured of staying in the same hotels or eating in the same restaurants. I once calculated that I played some 1,100 concerts during these four years. This represented for me not only an extraordinary musical experience in itself, but one of growth and maturity as a person.

The older men did not look forward to these tours which took them away from their families for long periods, often for nine weeks. One perfectly normal cellist, I remember, used to pretend that he was going crazy during the weeks just before a tour. The military police would find him sitting in a tree in the middle of the night, or something like that. I am sure the conductors were 99% sure it was all an act to get out of tour, but they could never take that 1% chance so the cellist always managed to stay home.

The tours followed a very regular format, seven days a week: travel by bus all morning, check into a hotel, afternoon concert of an hour’s duration, and a formal evening concert. The repertoire of each concert was the same day after day, which resulted in several idiosyncrasies characteristic only to tours of this kind.

First, playing the same music day after day contributed greatly to a disorientation of calendar time. Each day was like the last; only the hotel room varied. It will seem impossible to anyone who has not experienced such a tour, but on a tour beginning in September and ending in November the entire month of October did not seem to exist in the mind at all. There is no concept of day of week, and even knowing what town or what state you are in can seem unimportant. More than once, after a concert, I would have a member of the audience ask me what I thought of their town only to cause me to realize I had no idea what town I was in!

In addition to this characteristic of each day seeming like another, the older men had specific seats on the bus in which they always sat on every tour. Thus, I sat in the same seat of the same row, next to the same person, on ten of these tours. Since the older men also had “bus clothes” they always wore, once a tour began it soon seemed like a continuation of the last tour and in this way even seasons and years begin to blur.

Second, playing exactly the same program every day for nine weeks causes one, after about the second week, to begin to perform on a kind of automatic pilot. You begin to play in a state of semi-unconsciousness, unaware of the applause and only dimly aware of which composition you are playing. Somehow your mind continues to operate the fingers, supply the dynamics, etc., even though you might be thinking of home or school or even be in a near state of sleep. There was one older clarinet player, who actually slept through every afternoon concert. He sat buried in the middle of the section and would prop the bell of his instrument on the chair, use the mouthpiece to support his head, and hang the buttons of his sleeves on the clarinet keys to make it appear that he was playing. He would go to sleep and would wake up only at the end, which was the only time in an afternoon concert which the band members stood to acknowledge the applause.

The conductors also suffered from this phenomenon and so you would see by their faces that their minds were often on something other than the music. There was one concert, when we were angry over some issue or other, that we organized a plan for the Stars and Stripes Forever, which closed every concert. We played the introduction and then jumped to the final eight bars and I don’t think the conductor ever realized that we had not played the entire march. He was just aware of the beginning and the end. Oddly enough, I suppose because this piece is so familiar to everyone, the audience applauded and also gave no indication whatsoever that they had not heard this march in entirety!

With the entire band in this state of mind, the occasional local guest conductor who was invited to conduct a march must have felt he was conducting a recording, for no matter what he did, we played our tempo, our dynamics, and our phrasing!

I used to try to fight this mental state by inventing additional challenges to keep me alert. On one tour, for example, I decided to try to count the notes I played during a concert. The rules I set for myself were that I could only count the notes as I was actually playing them and if I lost count, as might happen in a particularly difficult technical passage, I had to wait until the next concert and resume counting from the beginning. I remember there was some passage which was so difficult that it took me weeks to be able to count through it as I played. I also remember being disappointed, when I was finally able to do this through an entire concert, to find it was not nearly as many total notes as I had assumed it must be. On another tour I set the challenge of memorizing my music, but only as I played it and in reverse program order. This meant that as I progressed on the tour I could begin to close and tie up my folder earlier and earlier in order to be able to immediately throw the folder into the music trunk and flee into the night as a free man.

Many of the career men occupied their minds somewhat differently during the tour concerts, namely attempting to make eye contact with ladies in the audience for the purpose of post-concert dating. One found, in an audience of several thousand, that there were always a significant number of ladies who came with the same purpose.

These Air Force years were marked by extraordinary, incredible and humorous events which seemed to occur daily. I regret I did not keep a diary during these years for I have forgotten enough funny stories to fill a whole book. I recall one summer concert by the Lincoln Memorial where our orchestra performed under the conductor of one of the other service bands. This officer, who was rather tightly wound, wanted to conduct the Stravinsky Firebird Suite. He appeared at our Monday rehearsal, opened the score (probably for the first time), saw the complexity of the music, and dismissed us without playing a single note! On Tuesday he returned with a manuscript score reduced to five lines of music, which he had ordered his staff arrangers to prepare overnight. We rehearsed a few minutes, but he had some difficulties and again rapidly dismissed us. On Wednesday he returned with a new manuscript three-line score and finally we read through the piece. The concert was the following day and I received a phone call from one of the copyists who was a friend alerting me to go up and look at the score during intermission. I did and was astonished to see the entire Firebird reduced to a single line of music, complete with cues!

On tour, given the general unhappiness of most of the men for being on tour in the first place, their sense of humor was often expressed in sardonic and even cruel forms. I remember one concert which we played in the great Mormon Tabernacle in Salt Lake City, Utah. It was a requirement of concerts in Mormon sites that a local person began the concert with a prayer. It was always the same prayer, which began by asking for blessing for the players and conductor, and then proceeded to request blessings for the mayor, congressmen, senators, and finally, the President of the United States. In Salt Lake City, an elder of the church, a man upwards of ninety years of age, gave this prayer and when he came to the end, instead of President Kennedy, said, “and bless President McKinley.” He suddenly grew silent, realizing that was the wrong name, but he could not remember the correct one. The band members on the front row began to feed him names of band members—”Freni” … “and bless President Freni” … “Seahofer” … “and bless President Seahofer,” etc. I could hardly contain myself!

The conductor of this band was Col. George S. Howard, a man of considerable experience. I have always regretted that due to the strict separation between officers and enlisted men which is maintained in the military I was never able to really get to know him at this time nor learn from him. The rigidity of this principle of separation is best exemplified by one visit to a military hotel in Honolulu. When one arrived at the private beach one saw a sign about twenty feet out in the ocean which read, “Enlisted men, left; Officers, right”—even though, of course, everyone looked alike in swim trunks and I presume the water of the ocean was the same on either side!

Another interesting and typical example of military thinking was an occasion when our commander announced that the base general had decided we should have a suggestion contest and that each of us must turn in a suggestion by a certain date. My roommate and I walked around the base and could see many minor things which needed to be fixed, such as an emergency light which had burned out—but we reasoned that the winner of this suggestion contest would be the suggestion which required the most under employed base construction persons to fix—changing a light would never win! At that time we rehearsed in a building which had earlier been a base movie theater, with restrooms adjacent to the front door. There were several occasions which we would have the wives of the higher officers listen to a choice of music which we might play for one of their charity events. My roommate and I noticed that at a certain angle in the theater, if the men’s restroom door was opened, one would have a brief view of the urinal. We, therefore, gleefully submitted a very formal paper suggesting that it was not in the interest of the band and our officers to have the wife of a higher officer see the men’s urinal! We imagined this would cause a major reconstruction of the men’s room and would guarantee the winning prize. Sure enough soon there appeared during our rehearsal a committee of construction workers and an equal number of supervisors to check out the situation. Then, to our utter disappointment, this inspection only resulted in the hanging of a cloth curtain in the middle of the men’s room, to hide the view of the urinal. Within a few days, however, any person washing his hands would turn and use the cloth curtain to dry his hands. Very rapidly this cloth curtain became filthy, resulting in another suggestion from us. And after all this, we won! A single cigarette lighter.

The reason I joined the Air Force Band, as my choice of service, was to be able to continue my education. True to promise, rehearsals ended by noon and I was free the rest of the day to go to school. Furthermore the Air Force paid nearly half of my educational costs, something for which I was very grateful since the pay of an enlisted man was quite small. Even with this help, I fell into a pattern of borrowing the money for tuition each semester and then just barely paying it back only to begin the cycle again, and so on for eleven semesters.

My original idea was to get a Masters’ Degree in history and theory, in order to complete my education in the areas in which I felt most weak. At this time Catholic University was the only school in the area which offered graduate degrees in these areas and so that was where I enrolled in the Spring of 1960.

Catholic University was clever enough to schedule all graduate classes in music in the late afternoon and evening, in order to attract persons such as myself from the four service bands. This meant that every class had a very strong student body. The standards were raised even higher by the nuns, who were very serious. They were persons typically assigned for life to Tucson or somewhere and the opportunity to take a leave to go to Washington to do graduate work was not only an honor for them but a release from their normal routine. Staying was dependent on their making high grades and, in addition, they were competing with nuns of other orders. They were very formidable to compete against in class.

In view of the large number of students from the service bands, Catholic University also had a policy which permitted unlimited absence, so long as one made up the work and passed the tests. So, in the Fall, I would have to tell the instructor that I would be missing the next nine weeks and they would always shake their head and say, “Well, I guess you can try.” I would always have some class member mail the class notes to me and I would receive these in hotels all over the country. It helped pass the time on the bus rides to be able to make up all the reading and so on each tour I would load the bus with a small library.

As time went on, it became evident that I could finish a Ph.D. during these four years and so when the time came to pay a $25.00 diploma fee for the Masters’ Degree, which I had completed, and being broke at the moment, I just skipped it and to this day I have a Ph.D., but no Masters diploma.

The final year and a half was spent writing the dissertation, which was the most difficult part. In the days before computers, when the major professor said, “Well, let’s rewrite it one more time,” it meant sitting at a standard typewriter and doing just that—one more time, typing page after page to make small corrections and additions. I was doing that until the week I left Washington. I remember after the movers had come, I was sitting on the floor with my rented typewriter finishing the final pages. In fact, if I recall correctly, I returned the rental typewriter on the way out of town to my first teaching job at the University of Montana.

Catholic University was the most conservative university in the nation at that time and the last institution to drop the requirement that the dissertation had to actually be published before the degree was granted. Until the class before mine, students had to go out and pay someone to publish the book and then the rest of their lives gave away copies as gifts. For my class, the new rules were that only one copy had to be submitted but the university could only take possession after one passed the final oral examination. I had planned to take orals during my final summer and then turn in the dissertation before I left for Montana. However, early in that final summer someone discovered a long overlooked rule that orals should not be given during the summer, for the reason that important faculty members might not be available. So it was necessary for me to fly back to Washington from Montana, on the first day of the Fall Semester, after having been in Montana only a week, to take orals. The problem for me was, what should I do with the dissertation in the meantime? It existed in a single copy (Xerox was not yet available) and I was both afraid to leave it with anyone or to drive across the country with it in my car (there was a story of a former student who did this and his car caught fire and he lost his manuscript!). Finally, in the week before I left, I went to the bank I had been using, filled out a deposit slip on which I wrote “One Dissertation,” and deposited it in the bank! The bank was astonished and amused, but agreed to put it in the vault.

Because of the ancient traditions of Catholic University, the final orals were a particular ordeal. First, in a tradition similar to posting marriage bans, several weeks before the examination they mailed a four-page program to universities throughout the nation to see if anyone objected to my achieving the doctorate. Of course, I didn’t know anyone anywhere else, but the period of waiting was nevertheless tense. Then, each professor, according to his role as the major professor, professors of minors, visiting non-music professors, etc., had a specific time for questioning. A time keeper with a large bell, would strictly police the times and if the bell rang during a question, I did not have to answer it. I was responsible for any question on any field of music, which means, of course, there is no way to really feel prepared. When this very formal session concluded I had no idea if I had passed or not, until the Dean stood up and addressed me for the first time as, “Dr” Whitwell.

My best friend and roommate during these years was Erik Shaar, a cellist, with whom I attended classes at Catholic University. We got along great and our mutual sense of humor made the entire graduate experience great fun. In the Forewords of our many term papers we would dedicate the papers to each other. For example, in the Foreword of one paper he wrote on the music of Max Reger, he claimed we were walking down the street and he heard me whistling a tune unknown to him. Upon his inquiry, he attributed to me the answer, “What, you don’t know the subordinate theme of the second movement of Reger’s Second Quartet?” And this, of course, led him to the study of Reger! I did the same kind of thing and the professors were always remarking how wonderful it was how we inspired each other.

On another occasion, we took a small book one professor had written, and forced every student to buy, on the Far East Tour. Wherever we went we would have some local person, a prostitute on the Ginza Strip in Tokyo, or a vagrant on Manila Bay, hold the book while we took a photo of the larger scene. Upon our return we made a great photo display, to show our fellow students and faculty the wonderful sights we saw in the Far East. Only the students looked carefully enough to observe that somewhere in the corner of every picture was the famous book. During our last summer, in the days when one could still buy great fireworks, we tied the book to a huge rocket, launched it, and blew it up somewhere high over Washington, DC.

Erik and I also made two wonderful camping trips to Canada during our periods of vacation. The most memorable was our visit to a small Eskimo village on the Hudson Bay. After the roads ended, the final 200 miles were traveled on a logging train through country uninhabited for a thousand miles on either side of the track. On the train were a group of young businessmen from Ontario who were officially visiting the Eskimo area for reasons relative to a forthcoming election. We could not help but notice their high state of excitement, which seemed odd to us given the remote destination. It turned out there was a government hospital for the Indians on an island in the bay which was staffed by young women from England. Since it was difficult to get nurses for such a location, Canada advertised in England, “See Canada, etc.” Once there, the nurses found themselves isolated for a year on an island with no white men. One can therefore understand that it was the intent of the young businessmen to jump off the train, hire a canoe, and go directly to the island. However, when we arrived a sign announced that the island was quarantined! So, for several days we saw these downcast men going about their political business among the Indians.

During our last year we were both applying for every college job in the country which was open. We both had the same problem of no experience and we grew increasingly alarmed as rejection after rejection came in the mails. Fortunately we both got jobs, he at the University of Northern Michigan and I at the University of Montana. Years later, at one of the big downtown hotels, I received the honor of being elected a distinguished graduate of Catholic University.

Also during our final year we each met the young ladies whom we married, in my case, Giselle Eckhardt, a piano major at Catholic University. She had been born in Germany, where her mother was a concert pianist, and after the war her family moved to Bolivia. She completed her schooling there in a German school and came to the United States to do her college work. As she graduated also in this same year, 1962–1963, we originally planned to be married during the summer. However, she wanted to teach a year and so we were married after my first year of teaching at the University of Montana (UOM).

Notes

- Beethoven, Piano Concerto No. 3 in C Minor, op. 37 (1800) ↩︎