My parents drove me to Ann Arbor in August 1955. Upon arriving I remember taking their car and driving to the home of Dr Revelli, where I announced something to the effect, “Here I am!” Naturally he was somewhat nonplussed at this appearance of a freshman at his door and I recall his welcome lacked warmth! On the other hand, a few weeks later a very strange thing happened. Revelli comes up to me and said he would like to give me private conducting lessons. Having not even had the elementary conducting class yet, I thanked him and turned him down. It was an odd experience.

After helping me get settled in the dorm and saying goodbye, my parents dropped me off on a street corner with my French horn. I was standing there, intending to find the music building to practice, when who should the very first person walking down the street toward me be but H. Robert Reynolds! Bob was a senior, a prominent student, and also a horn player. He immediately invited me for a coke, an invitation I sensed was due to his curiosity about finding a new horn player. He immediately advised me on a variety of important topics, introduced and made me a part of the best group of students, and was my role model in absolutely everything. It was the beginning of a very long friendship and I often have reflected on how lucky I was that he was the very first person I met at the University of Michigan!

Because my background in music had consisted of nothing more than playing in a high school band, I found myself completely unprepared for the demands of the program at Michigan, especially in theory and ear training. Therefore my grades for the first three semesters were not impressive, but they improved dramatically beginning with the fourth semester and eventually my grade average rose to a level that I was graduated, “with Distinction.”

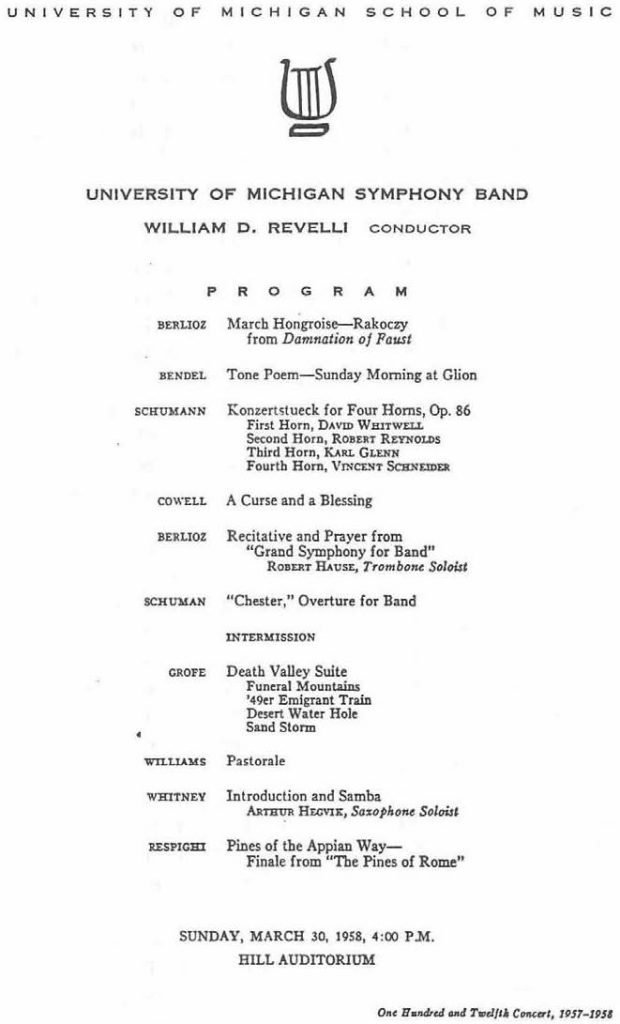

Looking back, I feel my classroom education at Michigan left something to be desired. There were some great teachers at Michigan, such as Hans T. David, the Bach scholar, but as an undergraduate student I was not permitted to study with them. Even Dr Revelli’s courses were limited to graduate students, so, even though I wanted to be a band director, my contact with him was limited to band rehearsals. On the other hand, the level of student was very high and I learned as much from the students as the faculty. One close friend was Howard T. Howard, who later became Principal Horn in the Metropolitan Opera, and it was he who first introduced me to and interested me in contemporary music. Another friend was Arthur Hegvik, who was older and had been in the army, and discussions with him first began to broaden my interest in literature and politics. The horn students were a friendly group and it was they who introduced me to taking a weekend train to Chicago to hear the orchestra with various great conductors, such as Bruno Walter and Fritz Reiner. Often we would have dinner with the Chicago horn players after a concert. And there were other playing opportunities on and off campus. This first year I got to play first horn with the orchestra which prepared the chorus for a May Festival concert, in this case the Schoenberg Guerre Leider.

Also, Ann Arbor was on the circuit for traveling orchestras and I was able to hear performances by the greatest artists in the world, including six by the Philadelphia Orchestra, and in this first year the London Philharmonic with von Karajan conducting, the Vienna Philharmonic and an orchestra from Munich. From the standpoint of the development of important musical ideas, my real education occurred sitting in Hill Auditorium.

The requirements for the bachelor of music in music education were so numerous that there were very few courses included outside the field of music. As a result, upon graduation I was keenly aware that I remained an uneducated person. It took many years of reading on my own before I began to feel a sense of general education.

Because Dr Revelli had obtained some financial aid for me, I was forced to participate in the marching band throughout these years. At first, of course, it was a great thrill to run out on the field before 100,000 people, but soon the damage of so many hours of playing the alto horn made this experience one I did not look forward to.

The Symphonic Band rehearsed during the evening during the marching season and then at the conclusion of football for two hours every day—ten hours per week! Years later I asked Dr Revelli how he was ever able to get so many hours of rehearsal into the class schedule. He replied that it was never scheduled for more than one period, from 4:10 to 5:00 pm, but he decided that since most people would not eat until 6:00 and would have nothing important to do during the 5:00 hour that he just continued his rehearsals until 6:00 and no one ever objected! As all students remember from this period, these were very painful rehearsals. Revelli would proceed literally one note at a time, seeking perfection in tone, intonation, and ensemble accuracy. I can recall one two-hour rehearsal spent on only the first five measures of a composition. I rarely recall Revelli speaking in terms of the components of the music, indeed, if someone asked a question like, “What chord is this?,” he would become very agitated and angry. I think this reflects only the nature of his own education and I later found in my study with Eugene Ormandy the same lack of confidence in discussing music. Oddly enough, both of them were in fact great musicians. It was just that their understanding of music was on a subjective level and one could only learn from them if one was able to absorb it on that level.

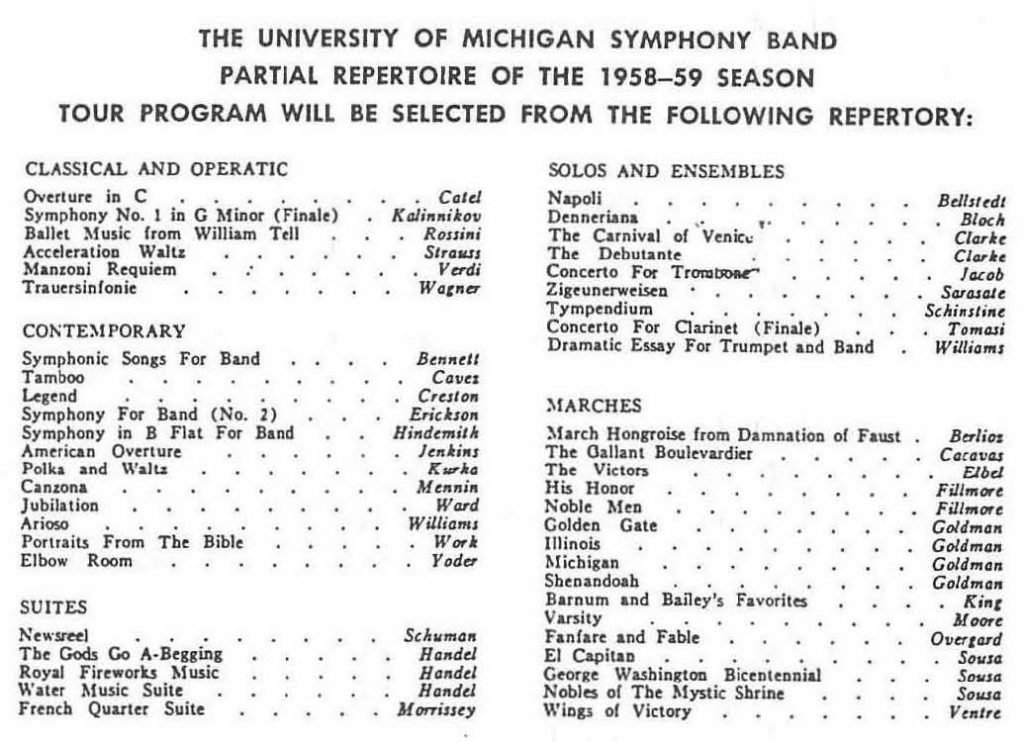

I think Dr Revelli probably performed more original band repertoire than most of his contemporaries in state universities. However, the repertoire of the Michigan Band, as I experienced it, also included trumpet trios, marches, transcriptions of minor orchestral works, and music of Broadway shows (see fig. 3).

My reaction to such a broad concept of repertoire was one of confusion regarding the aesthetic goals of the band medium itself, with the result that I began to seriously question whether I wanted to be a band director. In a letter to my parents at this time I wrote,

I don’t know about this teaching business. I just can’t see getting a degree and going out and teaching band … I don’t think I would be using all my talents. I know that if I can I would like to play professionally a few years. I also have a strong tendency toward orchestral conducting and composing.

There was one interesting high-point during my first year. I was taking a speech class and was forced to participate in a campus wide oratorical contest. In the end I won this contest and one of the judges, the Dean of the Law School, offered me a seat in this famous law school if I would drop music and become a pre-law student. Only my lack of experience in the real world prevented me from understanding how unusual this offer was.

For the summer after my first year at Michigan I developed a plan of traveling around Oklahoma giving high school students lessons at $2.00 per hour. Only one teacher, in Stillwater, Oklahoma, was interested and so I taught there on Saturdays. My regular summer job was with a construction company digging ditches.

Beginning with my second year at Michigan I lived in a rooming house, with Bob Reynolds and others, next door to the music library. It became my habit, whenever I had a free hour, to check out a score and recording and practice conducting in my room. On one occasion I decided to make such a project of one of the great Strauss tone poems. When I went to the library shelf the score in question was missing, but next to where it should have been was a score called, Symphony for Winds. Given the kind of music I was introduced to in the Michigan Band, I was astonished to find this score. I checked it out and immediately took it to Revelli to ask him about it. The fact that he knew nothing about this major work for winds, composed by a master composer during his lifetime, made a very strong impression on me. I began at once, whenever I had a free hour, to go score by score through the entire library looking for similar “unknown” wind works. This was the beginning, of course, of a life work of searching for, editing, and writing about such music. In about 1957, after I had thus begun to become aware that there was in fact a great repertoire of original wind band music by major composers, I recall a discussion with Revelli in which I predicted to him that by 1980 college bands would perform mostly a repertoire of original band music. The following week another fellow student, and lifelong friend, Karl Glenn, told me that Revelli quoted this in his graduate wind literature class and ridiculed me for this thought. As it turned out, my prediction came true much earlier than even I had forecasted.

By my junior year I was first horn in the band and during the senior year first horn in both band and orchestra. From this period I began to develop rapidly in my confidence as a musician. These experiences were facilitated by my good fortune in Carl Geyer of Chicago having made an exceptional instrument for me.

Among my teachers, Dr Revelli was certainly the most influential. He was in many ways a great teacher. When one saw him give a clinic on a subject such as beginning instrument classes, one saw the very best clinic of its kind available anywhere. He was always helpful to me and during my last two years at Michigan began to devote extra time to me, such as allowing me to conduct both the Symphonic Band and Marching Band in public, which was something unusual for an undergraduate student. He also offered to give me private conducting lessons, an offer which I did not have the courage to accept. He remained unfailingly supportive of me during my entire career.

Two other teachers were exceptional. Elizabeth Green taught beginning conducting and she had the ability to teach on a very clear and practical level. She was always very interested in me and asked me to proof the draft of her book, The Modern Conductor.1 In the first edition, she was generous enough to credit me for helping.

The orchestra conductor, Josef Blatt, was a European with professional experience and made all of his students aware of the highest levels of musicality. He also allowed me to conduct the orchestra, in rehearsal, in symphonies of Brahms and Tchaikovsky, which was, of course, an extraordinary experience.

It was during my second year that I wrote my first composition, a Concerto for Piano and Band. It created a lot of interest among the students, but it was never performed and I later threw it away.

The three summers of my university days were all extraordinary. The summer after my freshman year the only job I could find was digging ditches for a construction company in Oklahoma. I joined my first union, The International Brotherhood of Hodcarriers of America! It was very difficult work, digging in the hard Oklahoma clay in one hundred degree temperatures. But it was interesting getting to know a level of society I would have never otherwise come into contact with.

After my sophomore year I was invited to study with Mason Jones, Principal Horn with the Philadelphia Orchestra. At that time the orchestra had no summer season and so Jones would spend the summer in his childhood home, with his parents, in Hamilton, New York, a small rural town with an almost eighteenth-century flavor. The original plan was to take a couple of lessons per week, but he grew bored and, neither of us having anything else to do, soon the lessons were daily and lasted for hours. During the time I was there I think I literally played with him the entire repertoire of the horn, as it was then known—every etude, every sonata, every concerto. Jones was one of those unusual persons who was just “born” for the horn. He had picked it up for the first time in college and by his third year in college was already in the Philadelphia Orchestra! Having never experienced himself the question of solving technical problems, of which I had many, he really had little to say on this subject. On the other hand, he was a great musician and as we made our way through the repertoire, from Mozart to Hindemith, his musical insights were extraordinary. He changed my whole understanding about music and from this experience I have drawn idioms of interpretation until the present day. He would accept no monies whatsoever for this summer of daily lessons, and so it is in more than one way that I feel very much in his debt.

At the end of the summer I finally got up the courage to inquire about my potential as a professional horn player. There was soon going to be an opening for third horn in the Philadelphia Orchestra, so I asked him could I be considered? His answer startled me. “No,” he said, “while you certainly play well enough I would never look for someone like you! I am not so concerned how the person plays. What I will be looking for is someone who has no personality and no ambition.” A “potato,” I think he said. He went on to explain that as first horn the last thing he wanted was some young hotshot who would be breathing down his collar all the time. This was the first occasion I learned that the phrase, “May the best person win,” is an ideal outside the realities of the professional world.

I also asked him what I should do next in my education, since, as I indicated, we had gone through the entire horn literature. Again, his answer startled me. His answer was that I should study all the string quartets of Beethoven. Without knowing why, I did and when I had finished this project I understood his very valuable lesson: that acquiring musical understanding depends on absorbing a great deal of musical literature.

After my junior year of college I auditioned for and was accepted as assistant first horn in the American Wind Symphony in Pittsburgh, an ensemble of fifty-seven of the finest young wind players in the nation. My colleagues here contributed a great deal to my education and outlook. The repertoire of this ensemble was almost entirely original wind music and it was here, rather than at Michigan, that I came in contact for the first time with such masterpieces as the Bruckner E Minor Mass,2 the Gounod Symphonie, and the works of Mozart and Strauss.

The afternoons were free and these I spent in the local, and original, Carnegie Library. They had a great collection of scores and recordings and I absorbed an enormous amount of literature during these weeks.

The expected model for the undergraduate instrumental music major at Michigan was to obtain a teaching credential and then go into the public schools to teach. Only after this experience was it appropriate to think of a Master’s degree. In my case, by my final two years I had begun to feel a profound anxiety about this lock-step expectation. First, I was no longer excited about being a band director in the public schools and following the model held before me. Second, I was becoming keenly aware of the inadequate musical education I was receiving. There was a voice in the back of my head which kept telling me that, in spite of my good grades, I did not really know anything about theory and music history. I had been given an education consisting mostly of endless courses of outdated teaching materials. This being the case, even though I felt the equal of my peers, I had a deep fear of going out to some little town, being “Mr Music,” and having a student ask me a question about music which I could not answer.

At about this time I had the opportunity to meet Robert Ricks, a Michigan graduate, who was in the Air Force band and was obtaining his Master’s degree while in the service. Since at this time everyone had to go into the service one way or the other, his example suddenly offered a solution to my predicament. This offered a way to avoid going out to teach, to continue my education, and to take care of the service requirement all at once. Eagerly I discussed this plan with Dr Revelli, who informed me that if I did not get the experience of teaching in the public schools I would never get a college job. While, as it turned out, my first job was a college job, he was not far from the mark. There have been more than one university positions which I lost because I did not have this experience on my resume. Even as late as 1992 this question came up, even though even if I had had this experience it would have been a quarter century before, during which time the profession changed so dramatically it would have rendered the experience completely irrelevant!

During my senior year of college I had been invited by Max Pottag to be a member of an ensemble of seventy-six horns which would be playing for the Midwest Clinic in Chicago in honor of his seventy-sixth birthday. His former students, many of them professional players, gathered from throughout the country for this event. I was assigned to play assistant first horn and as it turned out the first horn got drunk and did not show up so I had the thrill of playing the solos in this august concert.

While in Chicago I auditioned for the assistant conductor of the Air Force Band in Washington, DC, and was accepted to fill the assistant first horn position in that group beginning in the Summer of 1959. Suddenly, I had a future.