In 942 ad, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle mentions a settlement, already 250 years old, called Hwitan Wylles (“the shining stream”). Reflecting the fact that our name is older than the English alphabet as we know it, the family were Saxons in Germany before this period and even earlier were Vikings.

In the Domesday Book of 1086 AD the name becomes “Witeuuelle” and by the late twelfth century “Whitwell.” This Derbyshire village has existed continuously and has a Norman church with some Saxon stones and with a Saxon font. My family can be traced to that period when people such as Thomas de Whitwell, of 1190, took the name of the village as their last name; they were the first persons in our family to have two names. There are today in England still six or seven villages and parishes named Whitwell and until the eighteenth century there were hundreds of persons with this family name living in England.

Two brothers, Robert and John Whitwell, left England in 1757 for America. Robert Whitwell, the first in America of my line, apparently killed a man in the American frontier and returned to England. His brother, John Whitwell, remained and fought in the American Revolutionary War. Robert’s son, Thomas Whitwell appears in 1763 in Charlotte Court House, Virginia, as a guard at the county jail. He was my great-great-great-great grandfather. He had two sons, Robert and Thomas, Jr, born in 1771 and 1774. I believe he was killed, as a member of the Virginia Militia, in one of the early skirmishes with the British in 1775. His wife remarried a man named Hall and moved to Kentucky.

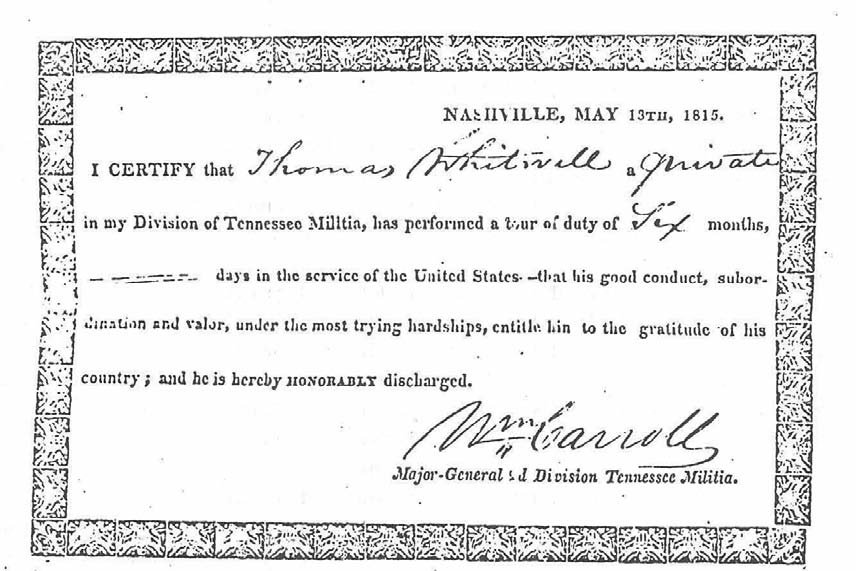

The infants were given out to other families by the Court and my ancestor, Thomas Whitwell, Jr, was reared in Charlotte Court House, Virginia, by a William Brumfield, who, by the way, was a great uncle to Abraham Lincoln. Thomas Whitwell, Jr, when he became of age, first went to Hanover, Virginia, which was then an international port where slaves were unloaded to work the great Virginia plantations. Thomas was there kidnapped to work as a crewman on one of these ships and sailed to Africa. On the return trip he jumped ship in Boston and made his way to Mercer County, Kentucky, toward the end of the eighteenth century. He became a successful farmer, owning land in several places in Kentucky and later in Western Tennessee, near the present town of Linden. During the War of 1812 he was one of the Tennessee long riflemen (fig. 1) who went with Andrew Jackson to New Orleans for the famous Battle of New Orleans. I own his powder horn which he used during this battle and on it is carved his name as well as the name and date of death of the famous English General Pakenham.

In the tradition of “notching the gun,” it is possible he shot the general.

Thomas Whitwell, Jr, had five boys, among whom was my great-great grandfather, Pleasant Whitwell, another successful farmer, landowner and County Clerk for Perry County, Tennessee. He was well-known in Western Tennessee as a primitive Baptist preacher, judge, and school teacher near the present town of Pleasantville, Tennessee, which is named for him. A History of Hickman County, Tennessee,1 written in the nineteenth century, recalls, “Whitwell was not only a good school-teacher, but was a good preacher and an upright man, who labored long and well in the Tenth District and surrounding country.”

My great grandfather was Elijah Houston Whitwell, who was killed in the Civil War at age thirty-five. Fortunately, for me, he had three boys before he left to join the Southern cause. They were my grandfather, John Randal Whitwell, Dr James Whitwell, who as an elderly gentleman, was run over and killed by an automobile at a time when there were only two automobiles in Tennessee, and William Whitwell, who with my grandfather moved to Texas in 1904.

My grandfather, whom I never met, was also a farmer and built a log cabin, where my father was born, in a valley which still appears on government maps as “Whit’s hollow.” He was a poor man with a very large family, of which my father was the youngest.

The poverty into which my father was born can be measured by the fact that he nursed until the age of four and did not own shoes until his fourteenth year. As a boy he walked two miles to a primitive one-room school house and when the family moved briefly to a farm near Denton, Texas, he finished high school in the institution which became the University of North Texas. This early poverty gave him an attitude toward money which is rather rare today—in his entire life he never borrowed money, always paying in cash, and never owned a credit card. After his retirement he became rather wealthy in the stock market, but continued to prefer to save rather than spend.

My father first worked in a general store owned by his brothers in Mississippi, but inspired by a traveling evangelist, left to study theology at Phillips University in Enid, Oklahoma. He became a very successful minister and was well-known in the Southwest within his domination, The Christian Church, as a highly intelligent man and a great speaker. I can remember driving with him to make guest appearances in one of those prewar cars at a time when no roads were paved. He had an exceptional memory which enabled him to always speak without notes and he annually gave the entire Dicken’s Christmas Carol in public from memory.

In some ways, in spite of obtaining three college degrees, he retained the qualities of one of the last of the genuine pioneers. The skills he passed on to me, as father to son, are skills not required in the contemporary world, things like how to skin a squirrel, rabbit, or a rattle snake (each, by the way, a separate technique of some complexity). He was never comfortable with modern appliances. For example, he was very reluctant to use a telephone and I never once saw him actually make a phone call himself.

Given his primitive youthful environment and education, he never had any appreciation for any of the Arts and consequently never had any understanding or appreciation of any of my accomplishments in music. Neither did he ever come and see me play baseball or football, or congratulate me on early achievements. I never remember hearing him say he loved me, but that is the way men were in those days and I know that in his way, he did.

My mother’s family were German farmers who came to this country during the middle of the nineteenth century, moving west from Pennsylvania, to Ohio, and finally to Kansas. One attractive story about these young German farmers in Kansas involves the visit of some young ladies sent by worried relatives back East who thought the young men were of an age when they should be married. The day before the arrival of the young ladies, the men nailed their tin plates to their dining table. After the first meal with the visiting potential brides, the men, who were not interested yet in marriage, called the dogs in to jump on the table and lick the plates clean. The ladies left the same day!

My mother’s father, Ulysses Simpson Grant Miller, was educated in Hiram College in Ohio, where a former faculty member became President Garfield. Rev. Miller was also a scholarly and serious minister who served in a number of small churches in the states of Kansas and Washington. It followed that his daughter, my mother, knew an early life of very strict discipline. Her mother was a school teacher in Kansas before her marriage and I have her first teaching contract, dated 1892, which calls for her to teach a “term of five school months” with a salary of $32.50 per month. She still spoke and wrote German as her native language throughout her life and extant correspondence indicates she was actively involved with the development of Phillips University in Enid, Oklahoma.

My mother was a naturally gifted artist and I have several of her paintings from the 1920s. They are truly remarkable and, had she not given up painting upon marriage to be a help-mate in the church work, I have no doubt whatsoever that she could have become a famous artist. She was also a natural pianist, graduating with a degree in piano from Phillips University, and even at the age of ninety could still perform from memory repertoire, such as Liszt, which she studied seventy years earlier. During her marriage she wrote and published a number of religious books dealing mostly with programs for youth groups.

My youth was spent in the towns where my father’s calling took him, in Ardmore, Oklahoma, where I was born in 1937; Dallas, Texas; Hutchinson, Kansas; and Lawton, Oklahoma. Until I left home for college it was the church which dominated my life with the family. Not only were there three church services each week, but most evenings of my early youth were spent accompanying my parents as they “called” on church members in their homes. I don’t recall discussions of any subject but the church in the home and all questions of my deportment and entertainment were measured against what would be appropriate for the son of a minister. What would people think? If in later life I found no need to attend church on a regular basis, perhaps it was because I felt I had spent more time in a church by age seventeen than a normal person does in a lifetime.

While I have a few memories of Dallas, most of my vivid early memories are of Hutchinson, Kansas, where I began school. I remember childhood games not of “cops and robbers,” but of gun battles against Hitler and Tojo. These games were especially vivid because there was outside Hutchinson a prisoner of war camp for German officers. Their presence was enough to scare young boys, but I am sure today that those German officers must have been quite delighted to be so far from the war. Hutchinson, in the years during and immediately after World War II, was a tranquil environment almost impossible to imagine today. In a time before TV, I can remember the common experience during the summer of sitting on the porch and watching it rain as a form of entertainment! I remember my first four years of school there, and my friends, very vividly. During the first grade I was the subject of a serious discussion between parent and teacher over concern for my tendency to “day-dream” in class.

Looking back, I am quite confident I was merely bored with the educational demands, which was something I felt until graduate school. I do not recall ever having homework, even in high school. I do recall being bored during my free time in those early years and frequently entertained myself by creating various games in which I competed with an imaginary person. Being reared by educated parents, I find it very odd, in retrospect, that I was never encouraged to read books during this free time. There was a small public library walking distance from my home, but I do not recall ever going there. It is a supreme regret to think I could have had ten years of self-education reading biographies, history and travel stories, which I am sure I would have absorbed with great interest. I am confident my life would have taken a different direction had I better used that free time. My last two years of high school I worked for one of the original Dairy Queens, where being paid thirty-five cents per hour, I acquired the first money I was free to spend as I wished. After a year of hard work and responsibility my pay was increased to forty cents per hour! Interestingly enough, some money was already withheld for Social Security.

While living in Hutchinson, Kansas, I had my first introduction to music, first in piano study with my mother. I don’t recall how long I studied, but I have a composition I played in public at age nine of a level of difficulty such that I cannot play it today. My mother was a piano teacher with always twenty or more students who came to our home for lessons. The house was filled with the sounds of the beginning students and it played a role in my not continuing. I had too much piano in my ear. As the result of a family vacation to Gunnison, Colorado, in 1946, where my older sister was attending the famous music camp there, I was selected, at random, by Dr William D. Revelli, for a demonstration clinic on how to select an instrument for a child based on the physical attributes of the child. I should, he said, begin study on cornet, and so I eventually did.

I entered the fifth grade in Lawton, Oklahoma, where my father had taken a large church. Lawton was a much rougher, almost “old-West” environment and my male friends were fellows with little character or ambition. Involvement in the church, as well as scouting activities, in which I advanced to the rank of Eagle Scout, offered some balance.

During the eighth grade I resumed study on the cornet with James T. Matthews, a fine cornetist who was then the high school band director at Lawton High School.

I remember that at the first lesson he announced that there would be no set fee for the lessons, but that I would be charged five cents per mistake.

The initial lessons were costly, but parental pressure soon resulted in exceptional development. Within a year I was performing some of the “Characteristic Studies” in the Arban book. With the beginning of the ninth grade I dropped out of band in order to play football. I was on the first team and enjoyed the impact this had on the girls. However, once football season concluded the subsequent loss of “status” caused me to approach Matthews about getting back in band. I wanted to play baritone, which my best friend played, but I was allowed to re-enter band only on the condition that I play horn. I immediately became very interested in this instrument and formed the habit of practicing about four hours a day throughout high school.

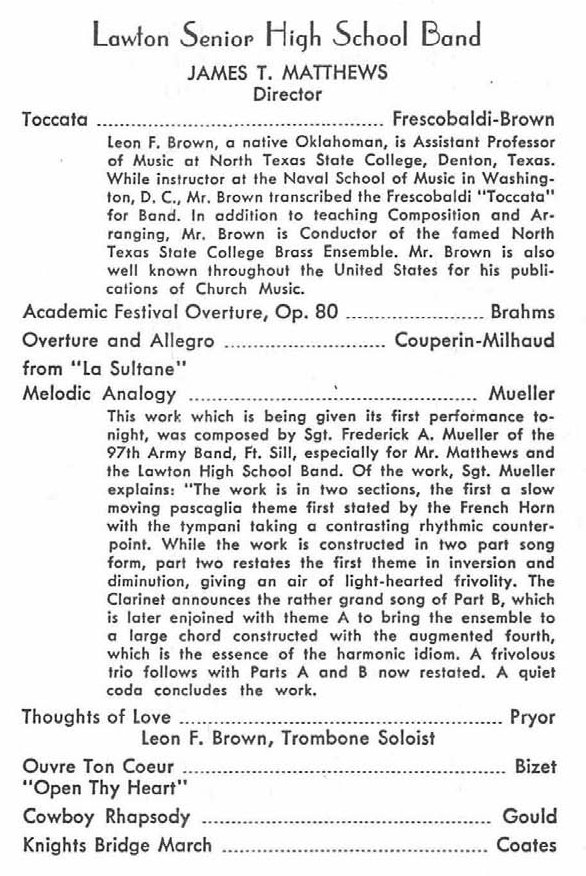

James T. Matthews was a very driven high school band director and consequently I had the good fortune to play in a very exceptional band (fig. 2). Much of his ambition came from his very gifted wife, Billy. She was an extraordinary flutist (all our high school flutists played Hanes!), beautiful, and with a wonderful personality. Her accidental death, just after Matthews had been appointed Director of Bands at the University of Houston, was something from which he never recovered.

Other than the quality of the high school band, I lived in an environment of little cultural influence. I never knew orchestras even existed until a girl friend in the tenth grade gave me a recording of Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony. Hearing this for the first time created an impact which I can still remember. I played it over and over, conducting to the recording. I began to buy more recordings and can still remember each new discovery—Beethoven, Franck, and especially Strauss.

In high school I was also active in debate, which developed my speaking skills. I was very successful in this and during the eleventh grade became one of the leading high school speakers in the nation, as determined by points awarded by the National Forensic League. I was selected to attend the National Student Congress, held in San Jose, California, where I was awarded the silver medal as the second highest scoring speaker in the nation. This debate experience was very valuable, aside from the public speaking practice, for learning skills in research and organization of material.

By high school I began to wonder how one decides on a career. I never remember anyone talking with me about careers and it seems odd to me today that I did not think of approaching the members of the church, which included doctors, lawyers, and a congressman. Lawton was an army town, lying next to Fort Sill, and for some time I was inspired toward a career as an army officer. But this was the period just after the end of the Korean War and the military was retrenching as no one could see any future role for the military. Officers I knew in the church strongly discouraged any thoughts of this as a career because with the end of the Korean War everyone saw only extended peacetime in the future, one characteristic of which would be no promotions.

I began to think of music as a career mostly because I was constantly being praised for my talent as a horn player. The crucial moment in what would become my professional life came at the conclusion of the tenth grade, when I talked about six fellow students into joining me in going to Gunnison for the music camp. I remember vividly playing for all the famous conductors, Al Wright, Mark Hindsley, Ralph Rush, and with Dr Revelli in the top camp band. The intensive musical environment was wonderful and I must have made a good impression for Clarence Sawhill offered me a scholarship to come to the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) as did Ralph Rush, head of Music Education at the University of Southern California (USC). Rush even offered me a room in his house to stay if I came to USC. But some of the students were going to the University of Michigan (U-M) and so I made that my choice. Revelli was also interested in my coming there and not only arranged a scholarship but cleared all obstacles.

I entered Michigan without taking a single entrance test of any kind.

But all this talk about universities that summer made me feel I was just marking time in high school so upon my return to Lawton I visited the principal and told him I wanted to graduate a year early. By taking correspondence courses and summer courses I was able, in fact, to skip my senior year and go directly to Michigan. My family had previously assumed I would attend Phillips University, as had my parents and sister. Not only was my musical education at Michigan far more valuable, but it enabled me to broaden as a person and shed the prejudiced and narrow-minded views of the Southern world in which I had been reared.

Notes

- Jerome D. Spence and David L. Spence, A History of Hickman County, Tennessee (Southern Historical Press, 1900). ↩︎